The View From A Ringside Seat

Reprinted with the express permission of Airforce magazine

By Jack McLean — as told to Paul Nyznik

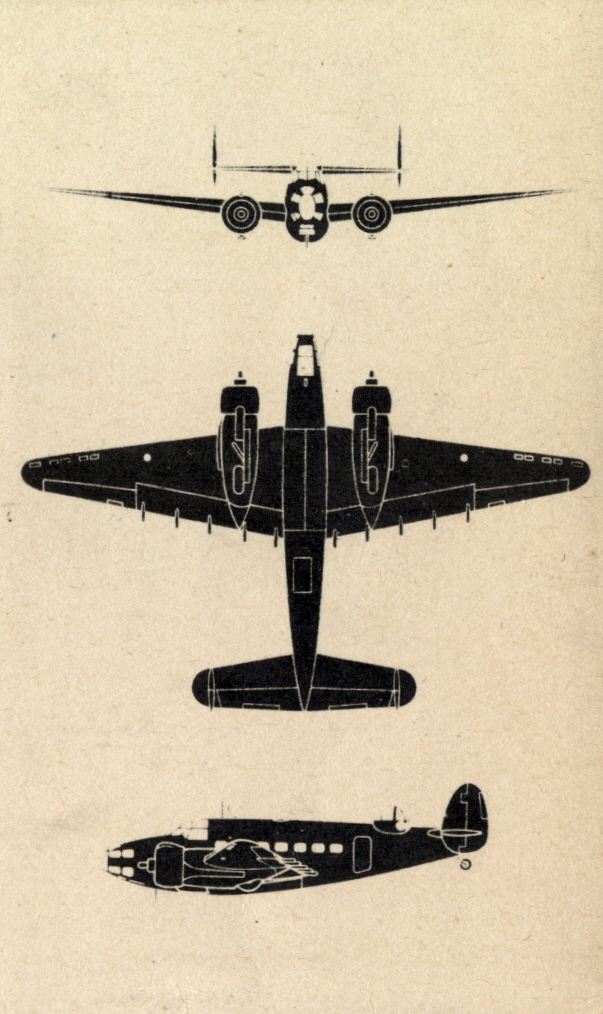

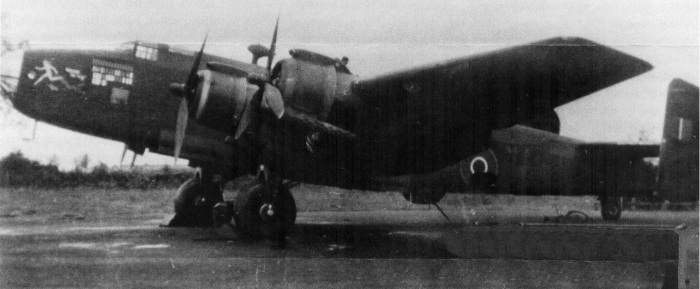

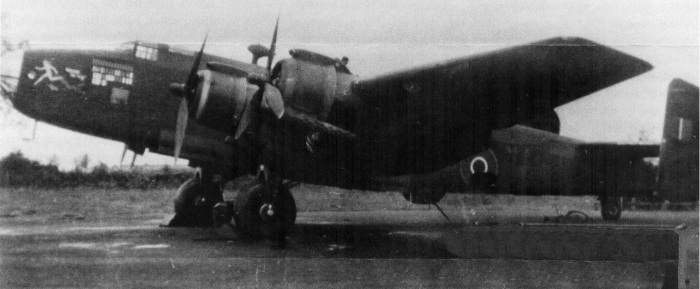

Halifax Mk III “Willie the Wolf” of 415 (Swordfish) Squadron which would carry mid-under air gunner Jack McLean on his tour-completing 32nd trip – a raid on a synthetic oil plant at Castrop-Rauxel, Germany on November 21st 1944. Note the mid-under gun position.

On the morning of a scheduled night mission, life on a bomber squadron in 1944 England stirs before dawn. And as the “new boy” on the squadron, I have already heard it all — about the crew failing to return from its first mission, from its “unlucky” 13th, its 31st — or any other number in between. In 1943-44 aircrew losses reached 55 percent — and I have heard that too.

My log book entry for Aug 7th 1944 shows:

Sortie No. 1 — Halifax Mk III — GU “V” — “Old Joe Vagabond.”

Skipper: F/0 Roberts Target: La Hogue, France.

Mission: Support advancing Allied ground forces.

Early morning, Aug 7th 1944 — Coded information for this night’s operation has been received from Bomber Command. The news that ops is “on” has spread and is now known to aircrew. Armourers begin to roll out bomb-laden trolleys. Ammunition boxes for the gun turrets are replenished. Fuel bowsers complete refueling of aircraft by mid-afternoon.

1400 hrs — Bombs are loaded and mechanics have made all final checks of ammunition feed for the gun turrets. Radios, electronics and engines have all been tested and indicate everything is ready to go.

1500 hrs — All aircrew who will be flying tonight are gathered in the briefing room. We sit, facing a stage and a huge curtain covering what we know is a large wall-map outlining tonight’s operation.

The CO enters the room. Everyone springs to attention. “At ease, gentlemen,” he says. “Please be seated.” He begins the briefing by pulling back the curtain, revealing the target. For destinations that are considered “not too hot,” there may be a slight sigh of relief. For those considered “hot” there would likely be pronounced “Ohs” and “Ahs.

Now we hear from the intelligence officer, who provides important information on the route to and from the target and details on the target itself. This will include all known intelligence on enemy defences and explanations as to how the proposed route, outlined in red tape, should avoid those areas as much as possible. He will identify the location of enemy fighter bases and those of concentrated flak. Crews are told where they will be required to join the main bomber stream en route to the target, the precise time of arrival over the target for each aircraft, operating altitudes, authorized radio frequencies and Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) colours for that night. The Met officer provides the latest information on en route weather, with particular emphasis on weather conditions to be expected in the target area itself.

With the briefing over, we are off to the Mess for the pre-trip breakfast of eggs and bacon.

1600 hrs — Crews are issued parachutes, Mae West life vests and escape kits. A lorry, usually driven by a pert member of the fair sex, takes us out to the waiting Halifax. Maybe a last cigarette will be enjoyed before boarding. After each pre-flight check list is taken care of, the skipper announces: “We’re ready to go.

1700 hrs — With a “Good Luck!” wave from our hard-working ground-crew, we move out from dispersal, taxi to the end of the runway and, within a few minutes it’s brakes-on, throttles full forward… brakes-off — and we are rolling down the runway, gathering speed.

I am seated on the floor, facing the rear, in my take-off/landing “crash position” with my back to the main spar. It seems to take forever as the “Hallie” strains to lift its 29-tonne maximum load of bombs and fuel. Then, almost imperceptibly, I feel the tail rise, we lift off, the wheels retract into their wells and we are on our way.

Safely airborne now, I leave my position at the main spar and head along the fuselage to the trap door in the floor, which covers the location of the mid-under gunner’s private “office.”

I pull open the double doors and ease into my seat in the cavity below. Reaching up, I drop both doors closed, leaving four or five inches of clearance above my head — and nothing but open air below. Now seated facing the rear and with legs splayed, I pull the gun toward my chest, into firing position. I feel ready. A bit apprehensive — but ready.

Imminent departure on McLean’s last sortie (No. 32).

At right is tail gunner “Red” Hennesey.

A word about the environment I call my office:

During a tour of 30 ops the air gunner on a bomber will spend hours static at his post. In my case this meant that I sat suspended amidships under the floor of the Hallie, often with little freedom of movement for the duration of the flight.

In some respects the mid-under (m/u) gunner’s position was unique. That is not to imply that it was a more — or less dan-gerous/difficult post to fill than that of the tail or mid-upper gunners. Only that it was different. Consider: it was an ap pendage built under a trap door in the floor of the aircraft, deep enough, in my case, to accommodate one, 5 ft 8 in, 128-pound airman and one .50 calibre Browning machine gun.

That area of the fuselage, viewed from the exterior, resembles a post-production afterthought. And that is pre-cisely what it was.

The Germans had developed for their fighters an upward-firing weapon they called Schragge Muzik (jazz music). Positioning itself, unseen, under the enemy bomber, it had the luxury of time deciding the opportune moment to unleash its attack. In 1943-44 the re-sulting loss rate in Bomber Command reached 60 percent — including occa-sions when the Luftwaffe fighters would join the gaggle of bombers as they re-turned to their U.K. bases, only to be shot down in the landing circuit. The mid-under gunner’s position, primarily on the Halifax B Mk III, was the Allied response.

But back to business: I am looking out into the open air. At our height of around 20,000 ft it feels bitterly cold, in spite of our electrically-heated suits, helmets and gloves. At eye-level I am able to cover the area between the 10 and two-o’clock positions, as well as an almost unobstructed view below. Soon I will be able to test-fire the Browning.

But as I wait, I cannot help but wonder, “What in heaven’s name am I doing here?” Less than a year ago I was an un-sophisticated teenager, anxious for ad-venture. I got my wish and on this night I am thousands of miles from home, in a strange land, in a Halifax bomber en route on my first operational mission.

I am blissfully unaware that in the next 106 days I will be asked to repeat the process 31 times.

On this day there were butterflies swirling around in my stomach, but once the Hallie began to roll down the runway, almost magically, the tension eased. I could feel it.

Dusk is gathering and, for a fleeting moment I pause to wonder if I will be numbered among those who will be re-turning this night. It was therefore with a huge, combined sigh of relief from the crew when we met no opposition from enemy fighters or anti-aircraft batter-ies and, in a total of 4 1/2 hours, we are safely back at our East Moor base. It was not always that way.

Sortie No. 15 — Sep 15th 1944, Target: Kiel, Germany

We were on our run into the target when suddenly, from 2 o’clock low, tracers were coming at us, passing under and continuing upward between our fuselage and starboard wing. They travelled right under my position, lasting about three seconds — not even time to call for evasive action.

We were attacked again before reaching the target. Thank heaven both failed and the fighters didn’t hang around. Out of several hundred bombers on that raid there were plenty of other aircraft to occupy their attention.

I saw one Hallie go down. It was on our starboard and a few hundred feet below when what I assumed was a bomb from above tore off its starboard wing. I saw only three ‘chutes and it was going down fast; so that was the end of the war for four brave airmen. It was a sobering sight, which I have never been able to erase from my mind.

That op was a real nail-biter.

In early Oct 1944 we started to see two new night-fighters — the Messerschmitt 262 twin-engine jet (Swallow), a fast, well-armed aircraft — and occasionally the Heinkel 219. Added to the mix of Junkers 88 and Me 110, both with upward-firing guns, the new fighters proved very successful.

It has been my observation — perhaps a truism — that when you belong to a group of individuals who find them selves sharing an experience fraught with underlying, perhaps lethal danger, there occurs a special kind of bonding. Between two young men it is usually an unspoken bond, and one which may last a lifetime, regardless of how long or short (such as during wartime flying operations) that lifetime may turn out to be. In my case that person was Harold O’Connor, the brother I never had.

Of the scores of men and women who touched my life during the war years, and beyond, none had a more lasting influence on me than O’Connor. We first met at the recruiting centre in Ottawa in July 1943 and for the next two years were seemingly inseparable — throughout training in Canada under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), sent overseas at the same time, on the same excuse for a sailing vessel, both completing a full tour of ops as mid-under gunners on the same squadron, the same base, visits to Edinburgh and London (mutually favourite destinations on every leave); all without suffering so much as a scratch — in the air or on the ground.

“Huck,” as he was known to everyone but me, was the steady, quiet one of the duo. If there was a scheme to be devised I was usually the instigator, while he provided enthusiastic support and accepted equal responsibility for any consequences. In an environment where relationships could be fragile — and short-lived — ours was an enduring friendship which remained strong until Harold’s sudden death of a massive heart attack in 1999, aged 75.

When Harold and I decided to join the military there was no question but that it would be with the RCAF. Our sole ambition was to become members of aircrew. The specific role was irrelevant and when the selection board decided that we would be trained as air gunners, we were both delighted.

Air gunners’ graduation class, Mount Pleasant, PEI, April 1944.

Jack McLean is 2nd from left, front row.

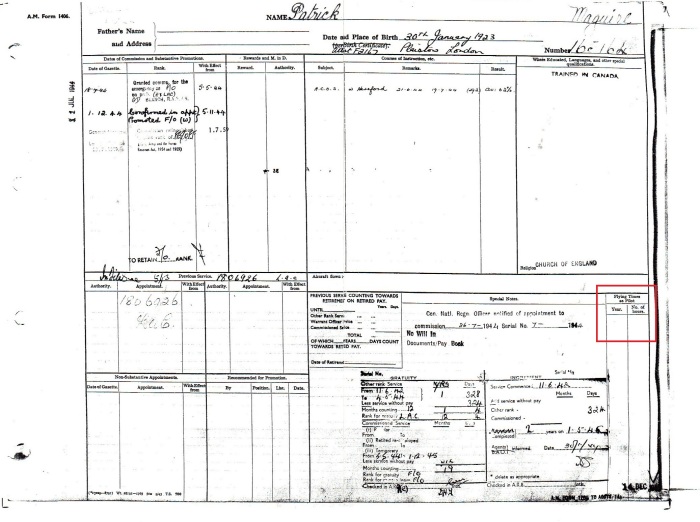

Recalling the situation as it was in 1943, the RCAF was experiencing severe manning problems in all of the aircrew trades — and that of air gunners in particular. The reason for that was clear: Each heavy bomber lost represented seven or eight highly-trained men. Such losses could not be sustained and the emphasis on recruiting air gunner trainees became a high priority. As so called “spare” gunners we would receive the basic training of all new recruits, followed by 12 weeks at a bombing and gunnery unit, presentation of wings and sergeant stripes to all graduates and, after a bit of leave, onto a ship for the seven-day trip to Liverpool.

Facilities aboard the RMS Andes were primitive at best. Crowded, unsanitary, and the food – admittedly a lot of it – most often of the poorest quality. Fortunately, we were blessed with beautiful spring weather so that during the day, when we were not on gun duty, we lounged around on deck. At night we slept, stacked five-high in canvas and pipe-frame bunks. It was a long, long seven days to Liverpool.

A course at an operational training unit (OTU), where bomber crews were normally formed, was considered un-necessary for us. This saved precious time and resources that Bomber Command could ill afford. Instead, we were sent directly to No. 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at Topcliffe, Yorkshire and introduced to the Halifax B Mk III and its mid-under gun position.

Unlike any of the other aircrew trades, the full training period for a “belly gunner” was relatively short:

Pilots: 43 weeks

Navigators: 43 weeks

Tail or mid-upper gunners: 37 weeks

Mid-under gunners: 20 weeks

Our transfer to 415 (Swordfish) Squadron RCAF followed and there Harold and I, and a dozen others, remained for the next 5 1/2 months, fully employed on operations.

Sortie No. 27 — Nov 2nd 44, Target: Dusseldorf, Germany

This city was a major industrial centre in the Ruhr Valley and an important inland port. Over 900 aircraft went there that night and the city was soon ablaze. I will never forget the sight. But for me it was unforgettable for another reason: It was the night I dodged the bullet.

I had flown to Oberhausen with a F/0 Regimbal the previous night and was listed for the Dusseldorf mission with him. Instead, I was sent with a F/L Little, which proved to be a very fortunate change of assignment. Regimbal and his crew were not so lucky. They ran into problems and their Halifax crashed and blew up in the Monschau Forest in Belgium. Again, but for the luck of the draw I could have gone with a F/0 Knobovitch — who was also lost that night.

This entire event was very sobering, making me realize the hazards of our job, and that the end could come, without warning, at any time. That 27th trip made me start wondering and counting the number of missions I needed to complete my tour: Three? Four? Five? It was never certain when you would be screened.

Lack of Moral Fibre (LMF)

I have sometimes been asked if there were occasions during operational flying when I had had enough and considered requesting re-assignment to ground duties. The short answer is “No.” But I understand what could drive an airman to that point and I believe it had less to do with a lack of moral fibre and everything to an individual having reached his own personal, psychological breaking point.

Of course, the prospect of being killed was always there, but if you dwelt on it your usefulness to the mission would be over. I think we were all familiar with the concept of LMF and the air force method of handling such cases. We knew that the consequences to the airman would be pure hell — so severe in fact that a member of aircrew would choose to go down in flames rather than “go LMF.”

It was a topic you never heard openly discussed. And individual religious beliefs aside, the philosophy of most active aircrew at that time is best expressed in the 91st Psalm:

A thousand shall fall at thy side;

And ten thousand more at thy right hand;

But it shall not come nigh thee.

My last op came on Nov 21st 1944 — a night raid on Castrop-Rauxel, a synthetic oil plant in the Ruhr.

With the reassuring roar of the four Bristol Hercules engines, with their combined 6,460 horsepower at my back, I felt in good hands. I was confident that this, my 32nd trip over Europe, would be a fitting climax to an unforgettable — if at times hair-raising — adventure of my life. I was right.

I was assigned to fill the belly gunner’s position on Halifax “Willie the Wolf,” with skipper F/L Lindquist and his regular crew, complete except for my friend Harold O’Connor, who had flown most of his mid-under trips with Lindquist up to that point. His absence this night puzzled, and disconcerted me.

This was my first trip to Castrop-Rauxel and the outward leg was uneventful — until we approached the target. I was shocked when we were coned” with searchlights and I

thought, “here I am on my 32nd and probably last trip and I’ll be getting the chop!”

I shall never forget those lights. Sitting there in the under-belly they seemed to be aimed and coming straight at me, personally. The skipper immediately took violent evasive action in a corkscrew manouevre, as we all prayed to get away from those blinding lights. We were losing precious height very fast and I remember trying to get hold of my chest-pack ‘chute, which was mounted in front of me in a holder to my left.

Under normal circumstances it would have been within easy reach, but I was pinned under the “G” forces and couldn’t move a muscle. If we had continued to lose height at the same rate, I knew that within seconds we would hit the ground. No question in my mind about that. But the skipper pulled us through.

We reached home more or less without further incident, seven hours after take-off, following what turned out to be the longest — and scariest — trip of my entire tour.

The next day our gunnery leader informed me that I had completed my tour and would soon be returning to Canada. Welcome news, indeed.

(Ed note. Jack McLean lives in Bells Corners, in suburban Ottawa. Retired F/L

Paul Nyznik, CD, of Nepean, Ont, is a former navigator with 435 and 408 Squadrons

RCAF. Both are members of the Air Force Association of Canada.)

Flying Officer Jack Mclean in 1946

Jack McLean in 2007