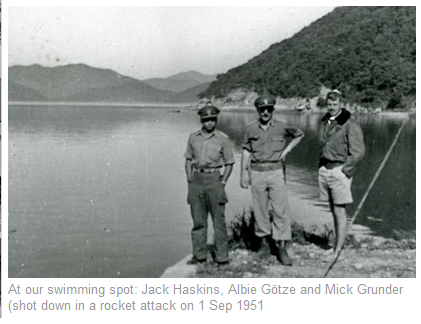

While searching for information about 137 Squadron and Albie Gotze, I found this…

You can tell that flying the Hawker Typhoon was no piece of cake…

A Supermarine Spitfire Mark IX raises the dust as it taxies past a Hawker Typhoon Mark IB of No. 181 Squadron RAF, at an advanced landing ground – probably B2/Bazenville – in Normandy. The Spitfire is fitted with a 45-gallon ‘slipper’ fuel tank.

Link

Martin Pederson — Typhoon pilot (source)

Martin Pederson had a good long “think” about it … and came to a conclusion. If he was going to be of any use as a fighter pilot, he had to give up this idea of wanting to survive, and resign himself to dying. That was the only way, he figured, that he’d be able to do his job.

It was 1944 and the young Canadian’s job was flying a Typhoon fighter-bomber on coastal strike duties for the RAF’s 137 Squadron.

As he put it 53 years later, “unless I could get control of my emotions, I was a dead duck! “It was an usually sober realization for a 22-year-old to make, a crucial milestone in a journey that had begun in June 1940, when Pederson (from Hawarden, near North Battleford) enlisted in the RCAF. He passed through No. 7 Initial Training School in Saskatoon, then Elementary Flying Training School in Virden and Service Flying Training School at Ottawa, where his wings were presented by no less than prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King.

By 1942, Pederson was headed overseas to Britain and a posting as a fighter pilot. He trained on Hurricanes and Curtiss Tomahawks before joining 137 Squadron, flying the mighty Hawker Typhoon.

There were two models of Typhoons: one carrying rocket projectiles and the “Bombphoon”, rigged for two 500- or 1,000 lb. bombs under its wings — the only single-engined Allied fighter, he was told, capable of carrying such a heavy load.

To make that point, Pederson recalls being at RAF Manston in Kent when a damaged USAAF B-17 came in. Talking to its crew, he learned that it carried only two tons of bombs. Figure out the economics: 10 men aboard a B-17 carrying two tons of bombs vs. a Typhoon, one man and one engine, carrying one ton of explosives. “Of course, being Yanks, they wouldn’t believe that!”The Typhoon’s engine was the formidable 2,500-horsepower Napier Sabre that, with a 14-feet, 10-inch propeller (“the biggest of any fighter of the war”), produced considerable torque. “They were a seven-ton bandit, to put it mildly; they were the only fighter aircraft of the Second World War, that I know of, that when you were posted to Typhoons, you were told that if you couldn’t handle this thing, you would be quietly posted off the squadron.”

The “Bomphoon” version was used by the three Canadian squadrons (438, 439 and 440) of the RAF’s 144 Wing.When taking off, “if you weren’t very careful opening that throttle, that thing would just take it — and you — off to oblivion.” So when Pederson, who had logged time on Hurricanes and Kittyhawks, got ready for his first Typhoon flight, he lined up on the left side of the runway, and started to pick up speed. He felt the aircraft swinging to the right, so he applied more and more rudder, which “didn’t do a damned thing”. By now, the rudder is “pretty well jammed to the floorboards and it’s still drifting”. When he finally took off, he was “at right angles to the runway with one wheel dragging.””You can imagine the scene: it was headed for a hangar and all the groundcrew were running!” But 10 or 15 minutes in the air taught him “what a wonderful aircraft it was”.”It was fast and the engine could take considerable abuse, providing nothing hit the radiator because they were running very hot … if you pierced the radiator, 30 or so second later, the coolant was gone and 30 seconds later, the engine seized.”

At any given time during daylight, 137 Squadron, then stationed at Manston, would maintain three pairs of aircraft at readiness: two aircraft on one-minute alert, two on five-minute alert and two more on 15-minute alert. One particular day, one pair was “shot off”, then another pair, and finally Pederson and his wingman found themselves heading toward Le Touquet, a harbor just south of Boulogne. Seven German R-boats (gunboats) were reported steaming toward the French port.

“There was nothing but silence and I thought that we were going back because it was too dangerous.”At this point, the other Typhoons started heading back to Manston; neither pair had attacked. “Hullo, Yellow 2, I think we’ll proceed,” said Pederson’s wingman, an experienced New Zealander named R.D. Soames. “We’ll go and take a look.” Like many European harbors, Le Touquet was protected by a mole, or breakwater; a gap in the mole let shipping enter and leave.As the two Typhoons went in, “all hell broke loose,” Pederson recalled. “The sky was full of flak bursts from the previous four aircraft. You couldn’t see anything except the twinkling of the guns and I soon realized that mole had gun emplacements on it.”The radio crackled again: “I think we’ll have one shot at them,” Soames said. “And with that, he rolled over … nose back and went down.””I have to tell you I was scared to death,” said Pederson as he described the sheer volume of flak thrown up that day. “I have never been so frightened in my life. To face that flak and fly right into it … it just seemed like total destruction.”So unnerving was it that Pederson admits he forgot his training and at 3,000 feet fired all eight rockets in a terrific salvo, then pulled back on the stick and climbed away — “the most stupid thing I could do because they were all shooting at me.”From the corner of his eye, he saw a plume of water far off in the English Channel. “That’s where my rockets landed because I’d pulled back on the stick too fast.”

Scary — but no less so than the next radio transmission from Soames, who said calmly:. “I’m just going in on a second run.” Pederson forced himself to follow, Soames picking out the first and Pederson the second of the R boats, letting loose with their 20mm cannon — and successfully sinking one ship each.Whereupon Pederson admits he did another “stupid thing”: he pulled up, looking over his shoulder at the shellbursts — and his engine stopped.Another big problem: the Typhoon’s huge chin radiator made a successful ditching almost impossible. Pederson was also getting down toward 1,200 feet, considered the minimum altitude for safely bailing out. He began undoing his seat harness, flipped on his radio and called, “Mayday!” so air-sea rescue could get a fix on him.By now, the French shore was out of gliding range, the Typhoon was juddering, “and I’m thinking that any second now, she’s going to hit. I must admit that in the last few seconds, I closed my eyes.”Now, RAF Manston came on the radio: “Aircraft giving mayday signal … please repeat . . . we didn’t get a fix.”Miraculously, the engine caught and started again. Pederson was able to keep it turning over “and when I crossed the English coast, I was at 18,000 feet!”

Pederson told this story to make a point: “so that you would understand the terror that pervaded everybody’s life”. He added: “I quickly realized that unless I could get control of that terror … well, the only way I could do that was to admit that you were going to die.”Once you’ve arrived at that situation, then you can function because you can ignore the fact that you’re going to die.”That’s why he spent the rest of the war thinking that “if you died, it will come quickly.”Wherein a contradiction: “You were safer and you’ve got to accept that — if you’re going to survive. And I honestly believe that one of the reasons why I’m here today is because I was able to control that terrible emotion. It’s something that absolutely grips you and you can’t shake it off.”

The scene now shifts to late 1944, when Pederson was based out of the airfield at Eindhoven in the Netherlands. The target were dams on tributaries of the Ruhr; Pederson’s squadron was assigned to take out flak emplacements. Because of the long distance to these targets, the Typhoons were to be fitted with 152-gallon drop tanks — a load of which was due in from the UK on Dakotas.”The instructions are coming with them,” the CO assured.The Typhoon’s fuel system was, Pederson recalled, “very touchy”; the long and confusing instructions did not arrive until midnight. “I stayed up all night memorizing them!”Next day, things went fine with the tanks, the flak sites were dutifully sprayed, “and the Bombphoons came in right behind us and knocked out three little dams. It added to the flooding … I gather it made quite an impact on the army when they tried to cross through that country.”

On another mission out of Eindhoven, Pederson was leading a flight of four Typhoons to sweep the Ruhr Valley and attack any trains they saw. Taking off, they entered cloud at 50 feet, slipped into line abreast and broke back into sunlight at 10,000 feet. Navigating by dead reckoning, they let down through cloud, broke out at 100 feet, “and we were smack dab in the middle of a city”.”I’m frantically thinking to myself, “Where in hell am I?” The Typhoons slipped into line astern, “and with that, what must have been obviously the city hall loomed up in front of me.”The Typhoons circled, “just dragging their wings on the rooftops”, zipped into open country, then roared over another urbanized area, where they spotted a railway roundhouse and eight engines waiting. Shooting up the anti-aircraft emplacements on the roundhouse roof, Pederson took aim and unleashed a full salvo of rockets — which missed the engines, but hit the base of a nearby smokestack, “and then it came down right across the backs of these engines!”

A successful mission — but when the pilots got back to Eindhoven and made their way to the intelligence officer’s tent, Pederson heard one of them say, “Gee, if you ever get an opportunity to fly with Pederson, don’t do it because he’s crazy!”___Crazy? Well, badly stressed. “Needless to say, it wasn’t too long after that the doc spotted me and grounded me as medically and mentally unfit to fly.”A good thing, too. Pederson said it was calculated that the average lifespan of a Typhoon pilot was 15 “trips”. Pederson managed to log 93 of them. “When I left the squadron, my nickname was “Old Pete” and I was 23!” he said. “I was the oldest person on the squadron.”

When he attend a reunion of his wing, it was noted that no fewer than 151 Typhoon plots were killed during the D-Day operations alone. During the approximately one year that he was on the squadron, 71 pilots died or disappeared, Before him, only two pilots had completed a full tour: one was blinded in one eye, another went mad — and then there was Pederson, who had lost 45 of his 185 lbs. “I couldn’t sleep at night; I’d tear the sheets to ribbons because of nightmares. I was in pretty bad shape.”

As Pederson, who went on to a successful postwar life and eventual leadership of the Saskatchewan Conservative party, said of his wartime experience: “I was just grateful to get the heck out of there and survive.”

More on 137 Squadron…