Editor’s notes

You are probably wondering why I posted four links yesterday.

I wanted to show you something Clarence Simonsen sent me.

Death Comes At Night was written by Clarence Simonsen, and I posted this story in December 2014. Little did I know there was more to this story than history had recorded…

Original post

On the warm summer night of 17/18 August 1943, RAF Bomber Command conducted a precision attack on the German V-2 rocket test site at Peenemunde. This operation was code named “Hydra” [RAF Operation order #176] and used an advance decoy raid to Berlin in an attempt to draw away the German night fighters from the main target on the Baltic coast, 150 kilometers north of Berlin. The raid was unique in many forms, as it was conducted in very thin cloud cover on a bright moonlight night, with the bombers flying at a low altitude of 8,000 feet. The force of 596 RAF bomber aircraft would attack the V-2 site in three separate waves. It took time for the German defenders to understand the main target was Peenemunde and not Berlin, and this allowed the first two waves of bombers to strike with full force. As the final wave of bombers arrived over Peenemunde the German night fighters had arrived in force, thus the majority of the 40 bomber casualties [243 killed, 45 POW] lost over Peenemunde came from the last wave. The Canadian No. 6 RCAF Group was part of the last wave and they suffered the highest casualty rate [19.7] in Bomber Command that night, when twelve of their 57 aircraft failed to return, and sixty were killed. Three RCAF squadrons [419, 428 and 434] each lost three aircraft over Peenemunde and this is the story of the loss of one new Halifax Mk. V bomber from No. 434 squadron, which carried rare newly painted nose art with German words – “Todt Kompt Bei Nacht”. No photo image was ever taken of the nose art.

Lloyd Christmas was born in Hamilton, Ontario, on 21 July 1919, and during his youth, drawing and painting became a major part of his life. In High School Lloyd received his first instructional art lessons, which were interrupted due to the depression and family problems. Like many Canadian youth of this period, Lloyd was forced to leave school and go to work to support their family. He became an apprentice in a silk screen printing company, where the pay was poor, but jobs were hard to find and it gave him experience in the graphic arts.

Lloyd’s career in the RCAF began at a Manning Depot in Brandon, Manitoba, in early February 1941. He reported to Toronto Manning Depot the following month, and then two months guard duty at Camp Borden in June. In August he reported to Trenton – “they tried to make everyone a Wireless Air Gunner.” Lloyd was soon on a west bound train to No. 2 Wireless School in Calgary, Alberta. “Not finishing High School caused me many problems in the RCAF, long on art, but short on the math.” Lloyd failed the course and returned to Trenton, where he was sent for Air Gunner training, arriving at No. 6 Bombing and Gunnery School, just before Christmas 1941. Sgt. Christmas graduated Air Gunner on 2 February 1942, leave, marriage, and report overseas to Stormy Downs, Wales, advanced Gunnery course beginning on 24 May 42. On 28 June he crewed-up with P/Sgt. R. Wright at No. 22 O.T.U. Wellsbourne, flying Wellington aircraft. 1 October 42, conversion to Halifax bomber at No. 1652 H.C.U., joined No. 408 RCAF [Goose] squadron on 24 October. Lloyd flew his first squadron air to sea test firing [rear gunner] in Halifax DG239 on 26 November 1942. Beginning operations on 6 February 1943, Sgt. Christmas flew seven night operations as rear gunner with pilot Sgt. Wright, the last completed on 26 February, Halifax “J” DT769 to Cologne. This original crew was suddenly broken up due to the burn out of their pilot.

Sgt. Christmas next flew three night operations as fill-in for other crews. 4 April – Halifax “S” pilot P/O Harty, [rear gun] 10 April – Halifax “D” pilot F/Sgt. Wood, [rear gun] and 27 May – Halifax “R” pilot F/O Smith [mid-upper gun]. On 11 June 1943, Sgt. Christmas was assigned to fly to Dusseldorf with the crew of pilot Gregg McIntyre Johnston, from Rosetown, Saskatchewan. This veteran combat crew had their original mid-upper gunner killed and after this operation, the pilot ask Sgt. Christmas if he would join their band of comrades. Lloyd agreed to remain as their mid-upper gunner until the end of their operational tour. The following night the new crew flew Halifax “T” to Bochum.

In July 1943, three experienced aircrew were sent from No. 408 [Goose] squadron to help form the nucleus of No. 434 [Bluenose] Squadron. The crew of P/O Gregg Johnston became one of those selected for transfer.

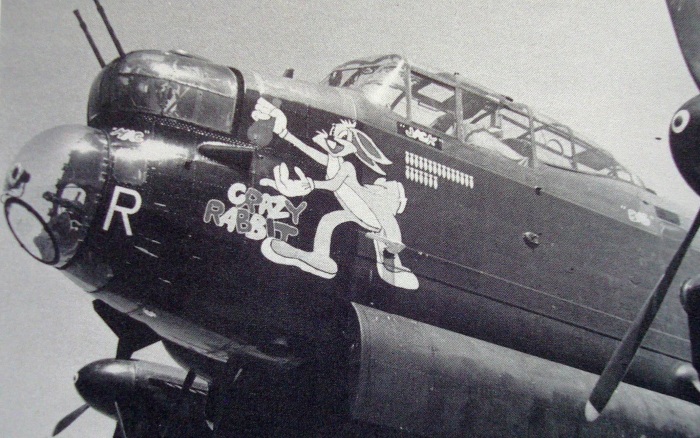

“I do believe we thought up the nose art idea of painting something while we gathered in a pub at Leeming, which was adjacent to 408 Squadron. It never came to fruition until we received a brand new Halifax “G” EB276, on our transfer to No. 434 [Bluenose] Squadron.” “We had quite a bit of free time while No. 434 was getting itself organized. We went on leave and I was able to go hunting on the squadron property. After training flights in our new Halifax, I had time to paint my very first [and last] bomber nose art. We had kidded with the idea of using the call sign “G” for German and that led to the idea of painting nose art using German names – “Death Comes at Night”.

I had to first scout around the base to find someone who could give me the German words needed, and I still don’t know if they were correct? I also had much difficulty painting with the coarse brushes, which I borrowed from other ground crew. When I finished the painting, the black German letters TODT KOMPT BEI NACHT appeared in a white circle and the middle of the circle contained a white skull and crossed bones.” “I will now describe what I remember about 17 August 1943. It was a rare beautiful sunny day and the flight engineer [RAF Keith Rowe] and I had ridden my motorcycle into a nearby town. Near lunchtime we returned to the sergeant’s Mess, which was alive with speculation we were going to the ‘Big City’ – BERLIN. When it came time for briefing the big wall map was opened, revealing the tape stretching from Flamborough Head, due east across Denmark and then a right angle turn south in direction of Berlin. The thing that surprised us most was that it went only a little distance south and then turned back west toward England. I do recall we were warned that if we failed to destroy the target on this first try, we would go back as many times as it took to get the job done. That was the first time any of us had heard a statement like that. I remember as we taxied out and started our take-off, I noticed there was an unusually large crowd of personnel lined up parallel to and back from the runway. Because of the light, the sun was just going down; they all looked like a big line of crows. I felt a sense of foreboding.”

“Over the channel we test fired our guns and sure enough two of my 303’s refused to fire. I was still working on them when we arrived over the target. We came in north over the Baltic coast and turned flying north to south over the target, dropped our bombs, then turned west on a course home. We were now attacked three times by three different German night fighters. The first attack came shortly after we left the target; a single engine fighter was spotted by our husky French-Canadian rear gunner Doug Labelle. He quickly gave Johnny instructions to corkscrew to starboard and we lost him. Immediately a twin engine, Bf110, attacked us and again we lost that one with a corkscrew.

Suddenly from far below and off to the port side, obscured by a dark patch of ground, a third aircraft fired cannon shells that arched up like big orange balls, directly into our port inner engine, just below me. Our Halifax seemed to shake and then flame poured from the engine and soon spread along the complete wing. Pilot Johnny gave the order to bail.” “Pilot Gregg Johnston maintained control long enough to allow his crew to escape; but he could not get out and was killed on impact. The crew was captured and the following morning the Germans took rear gunner Labelle to the crash site, to identify his pilot who was lying in the nose section of the Halifax. He was promoted to Pilot Officer posthumously and cited for valor.”

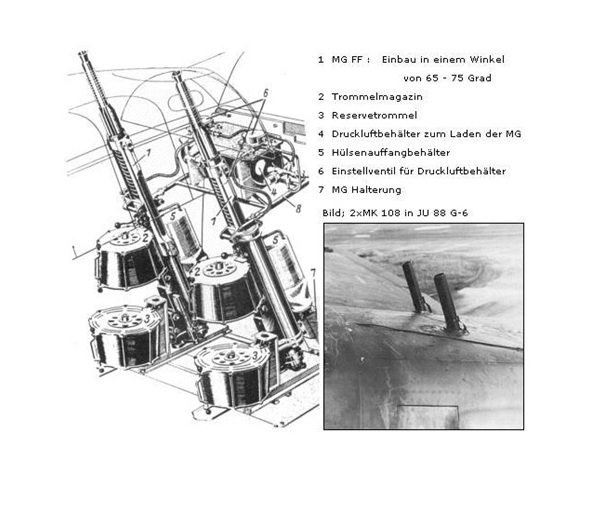

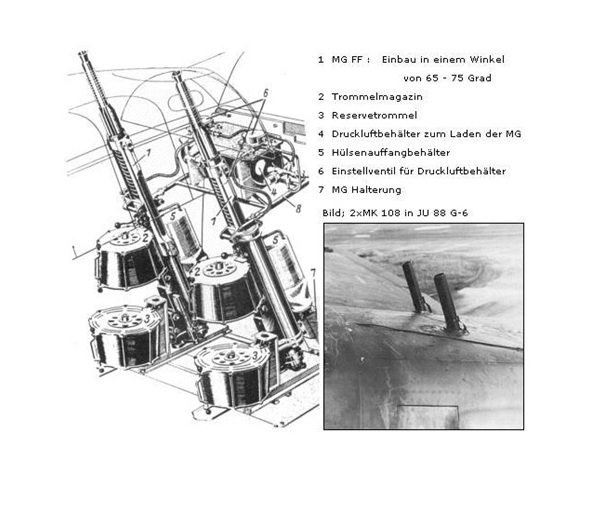

During the raid the Germans used their new “Schrage Musik” 2 x 20 mm cannon weapons for the very first time. The Bf110 aircraft was fitted with twin upward-firing cannons and this is what destroyed the Halifax Mk. V. The bomber crews had no idea they now faced danger from a night-fighter flying below them. Few aircrew saw the night-fighter, just tracer markers in the sky, then it was too late. Two of the new Schrage Musik Bf110 aircraft found the bomber stream and they shot down six bombers, including “Death Comes At Night.”

The deadly upward firing 2 X 20 mm canons aimed at 70 degrees.

When Sgt. Lloyd Christmas painted his little nose art on Halifax Mk. V, serial EB276, code WL-G, he had no idea how true his words ‘Death Comes At Night’ would become to the future Peenemunde history.

This first precision raid of WW II was conceived by the RAF to not only destroy the Peenemunde testing facility, but it was also directed at the living and sleeping quarters of the many technical and administrative staff and families as possible. The first RAF wave would bomb the 80 residential buildings at Karlshagen Housing Estate located on Usedom Island, home to the top 500 German scientists and their families. Because of the inaccuracy of the early Pathfinder aircraft, most of the first wave bombers [two thirds] dropped their bombs on the camp at Trassenheide, [two miles south] which housed [forced labor] foreign prisoners of war, killing 555. Although this part of the raid was not effective, two key figures, Walter Thiel and Erich Walther were killed together with their families, along with 50 residential buildings destroyed. The raid cost the lives of 735 on the ground but only 178 of the over 4,000 in the residential area were killed. The attacks came too late to effect the development of the A-4 rocket and gave the Germans the opportune time to move the rocket production to the infamous Mittelwerk center in the Harz Mountains. This would have a major effect on the future of man in space, American Russian cold war, the creation of NASA, and man on the moon.

At the same time as Operation Hydra, a group of nine Mosquito bombers conducted Operation Whitebait, the dropping of Pathfinder markings over Berlin. This was a complete success and tricked over 200 German night fighters to the defense of the German capital city. During this confusion, the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, General Hans Jeschonnek erroneously ordered Berlin’s air defenses to open fire on the German night fighters. On 18 August 1943, General Jeschonnek committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

The total Housing Estate was home to 1000 rocket scientists and over 3000 rocket personnel. If the first wave of RAF bombers had struck the intended target [F], the war and future space travel would have been altered. However the mistaken attack on the workers camp at Tassenheide [between rings #3 and #4] allowed all but one top German scientist to escape death. Only 178 rocket personnel were killed in the residential area, out of 4,000, which had little effect on future A/4 rocket development. This unusual operation left its mark in history, but never became the turning point it should have been. The continuous raids [post 18 Aug, 42] by RAF and American 8th Air Force against V-2 supporting facilities had a much larger effect on the A/4 future then the single attack on Peenemunde.

The Water Thiel family lived in apartment Hindenburg Road 56. They had escaped to the trenches in front of their home, but it took a direct hit by RAF bombs. Top rocket engine scientist Walter Erich Oskar Thiel was killed with wife Martha, daughter Sigrid, and son Siegfried. This one death did in fact cause a major setback to the future A/4 rocket development at Peenemunde. Eric Walther, Chief of Maintenance Workshops and family were also killed.

This post card shows the self-living model village housing estate constructed at Peenemunde, known as Karlshagen Siedlung. The construction was completed in October 1937, and housed 500 of the most brilliant German rocket scientists. Only one-quarter of the first wave bombers stuck this target late, destroying 50 of 80 residential homes. The occupants had escaped to bomb shelters, where only one top scientist [Thiel] and family received a direct bomb hit.

Had the RAF Pathfinder aircraft correctly marked this primary target, many experts technical and administrative, would have been killed. Three-quarters of the first wave bomber force struck the forced labor camp at Trassenheide, killing 555 prisoners of war. In total 18 of 30 wooden sleeping huts were destroyed. This mistake allowed the German A/4 rocket experts to escape to the bomb shelters and only two key figures were killed, Walter Thiel and Erich Walther. Post war interviews with German technicians [Helmut Zoike] even suggest the raid came at an opportune time, allowing the rocket production to be moved to the infamous Mittelwerk center.

In April 1943, Arthur Rudolph had endorsed the use of S.S. forced labor in the production of the A4 rockets in Peenemunde. In early June 1943, the first of 600 French and Russian prisoners of war arrived and began assembling A4 production machinery.

The RAF primary object was to kill as many expert A/4 rocket personnel as possible, including women and children, and this became a complete failure.

The facts in regards to the mistake of marking the wrong target have been covered in many publications by many authors. The RAF Pathfinders were the very best and on this moonlight night with light cloud covering they could not find the correct target? Is it possible one of the lead Pathfinder crewmembers could not bring himself to kill thousands of German women and children as they slept in their beds? The first causality in war is always the truth and the answer to my question may never be known. However, this bombing error did affect the future of world space travel, the Russia – American cold war, landing on the moon in 1969, and today’s space station.

A total of 243 airmen lost their lives that night over Peenemunde. The British lost 167 , Canada came second with 60, Australia 10, New Zealand 3, USA 2, Rhodesia 1, Trinidad 1, and Southern Ireland 1. Of the British total, 69 bodies were recovered from crashed bombers or washed ashore to be interred in British Berlin cemetery. Twelve bodies drifted east in the Baltic and were interred in Poland.

Today 125 aircrews are still listed as “Missing in Action.”

This story is dedicated to the unknown names and forgotten foreign prisoners of war who died on 18 August 1943. Their sacrifice changed the future world of space travel forever.

British R.A.F. map of the Rocket Base at Peenemunde 17-18 August 1943. Main targets marked in red.

A – Test stand VII, the main A/4 launch pad.

B – Peenemunde south, Production plant, where forced labor worked.

C – Dock for oxygen plant.

D – Test pad

E – Peenemunde East, development works

F – This area housed over 6,000 rocket engineers. The north section was known as settlement I; further south was the Karlshagen Estates, which housed the 500 most brilliant scientists. This was the primary target, but they bombed two miles south in ring 4.

Was this an error as recorded by all historians?