Jim L’Esperance, the son of Jim L’Esperance, sent me pictures of his father’s medals.

This is the first one.

And four more…

These also.

I am no expert on medals, but I am sure these medals will never be auctioned like William Stevenson’s medals were in 2004.

This medal was awarded to him by the U.S.S.R shortly before his death in 1988.

This means that Jim L’Esperance participated in protecting the convoys heading to Murmansk.

This is what I found on Stuart A. Kettles’s Website.

This is what is written…

In June 1941 Russia and Britain found themselves in alliance against Germany. As a result Britain agreed to supply the Soviet Union with material and goods via convoys through the Arctic Seas . The destinations were the northern ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. To reach them, the convoys had to travel dangerously near the German occupied Norwegian coastline. My uncle took part in Convoys JW55A and RA55A in December of 1943.

After the war there were many commemorative medals issued by various governments, of these, only one was approved for wear with real medals, The Queen did approve the Russian “40th Anniversary of Victory in the Second World War” gong, and it so appears in the Canada Gazette. Known locally as the Murmansk medal because a number of RCN sailors on that convoy were eligible to receive one.

This was found on the Veterans’ site…

I add a few pictures taken on the Internet.

The Murmansk Run

Canada’s merchant navy was vital to the Allied cause during the Second World War. Its ships transported desperately needed equipment, fuel, goods and personnel to Europe and around the world. The very outcome of the war depended on the successful transport of troops and cargo by the sea. Although there were no safe havens for the merchant seaman, the greatest number of ships and men were lost on the North Atlantic routes and the notorious Murmansk Run.

In June of 1941, the German military launched an offensive against the Soviet Union. Political differences aside, it was determined by the Western allies that any nation warring with Germany should be considered an ally. As a result, agreements were reached to send much needed military equipment and lend-lease supplies to the Soviet Union in order to assist in their fight against the Germans. The Soviet Navy lacked the capacity to transport the massive amount of supplies, such as military equipment, vehicles and other raw materials, so much of the transport and convoy escort work was handled by the British, Canadians and Americans. The fastest (but most dangerous) supply route was through the Barents Sea in the Arctic Ocean to the Northern port city of Murmansk. This Arctic supply route became known as ‘The Murmansk Run’. Due to the great military and political significance of these shipments, the Germans fought hard to destroy them, and as a result, more than twenty percent of convoy cargo was lost on The Murmansk Run compared with only a six percent loss of cargo shipped to the Soviets through the Iranian ports in the Persian Gulf.

Convoys sailing along the northern tip of Norway and through the Barents Sea were exposed to one of the largest concentrations of German U-boats, surface raiders and aircraft anywhere in the world. Attacks by more than a dozen submarines and literally hundreds of planes at one time were common. Due to the high concentration of Germans patrolling the region, and the fear of being attacked by prowling German U-boats, strict orders were given that forbade any merchant ship from stopping for even a moment.

The consequences of these orders only reinforced the danger of the missions as individuals who fell overboard had to be ignored, and ships could not stop to help comrades in distress.

In addition to the German resistance, the voyage was made even more treacherous as Mother Nature routinely unleashed her fury across the cold Arctic Ocean. Many of the convoys sailed The Murmansk Run in the winter due to the almost constant darkness which helped to conceal the ships. This advantage proved to be only slight as other problems, such as greater amounts of polar ice, led to difficult navigation and forced the convoy route to move closer to German occupied Norway. The temperature was often far below zero and freezing winds from the North could easily reach hurricane force causing the waves to swell to heights in excess of seventy feet. At such temperatures, sea spray froze immediately to any exposed area of the ship, and created a heavy covering of tonnes of topside ice which could cause a ship to capsize if not cleared away. Binoculars, guns and torpedoes froze, and the decks were covered with a smooth coat of ice which made walking nearly impossible.

The supply shipments began in late Summer of 1941 and merchant mariners from Canada served on Canadian, British and American ships (as well as ships of other nationalities) to support the supply convoys to the Soviets. From 1941 to 1945, forty-one convoys sailed to Murmansk and Archangel carrying an estimated $18 billion in cargo from the United States, Great Britain and Canada. Among the millions of tons of supplies were an estimated 12,206 aircraft, 12,755 tanks, 51,503 jeeps, 1,181 locomotives, 11,155 flatcars, 135,638 rifles and machine guns, 473 million shells, 2.67 million tons of fuel and 15 million pairs of boots.

The Royal Canadian Navy became involved in convoy escorts in October 1943, and from that time until the end of the war Canadian warships participated in about three-quarters of the missions. Canadian ships involved in supporting the convoys included the destroyers Haida, Huron, Iroquois, Athabaskan, Sioux and Algonquin, and approximately nine frigates from Escort Groups 6 and 9. None of the Canadian ships were lost while escorting convoys on The Murmansk Run.

Canadian Navy personnel had little contact with the Russian people. Layovers in the Murmansk area were brief, and few officers and men were allowed ashore. However, it is interesting to note that the first Canada-Soviet hockey game was held during a stopover in 1945 when sailors from the destroyer HMCS Algonquin played an exhibition hockey game against Soviet personnel. It is believed that the Soviets won the game 3-2.

Despite the dangers and hardships faced by the convoys sailing The Murmansk Run, the Allies were unanimous in their desire to keep the Soviet Union in the fight. It was feared that if the Soviets were conquered, as the Russians had been in 1917, the Germans would focus the majority of their forces in the West.

Because of the strategic importance of these supply lines, fierce German resistance, and extreme weather conditions, the merchant mariners and Navy sailors that sailed their vessels on The Murmansk Run are considered some of the bravest veterans in history.

This photo of IROQUOIS making smoke was taken on or about May 24th 1944 outside St. Margaret’s Bay, Nova Scotia during running up trials after refit in Halifax. In the foreground is wash from a motor launch. (This RCN photo was provided by John Clark).

HMS Mauritius is making smoke in this scene. This was not an exercise – it was the real thing. Both Iroquois and Mauritius were being shelled by shore based gun batteries. Both ships were straddled by shells as they approached the Gironde river area on the morning of August 22, 1944. This encounter was too close for comfort, so orders were given for a hasty retreat. The picture was taken from the bridge of Iroquois while she was also making smoke.

This was as closest Iroquois ever got to being hit. German gunners were dropping huge shells all around the ship. From a current day perspective, it looks like another wartime photo but to the crew of Iroquois, it was almost the day they met their Waterloo! Iroquois had a lot of close calls but she was a very lucky ship.

It was common practice to go in as close as possible to try and get the shore batteries to open fire. Upon exposing their positions, the air force would attack immediately. There was an old saying that if the ship had wheels, the skipper would take her up on the beach. (Photo courtesy of Jim Dowell)

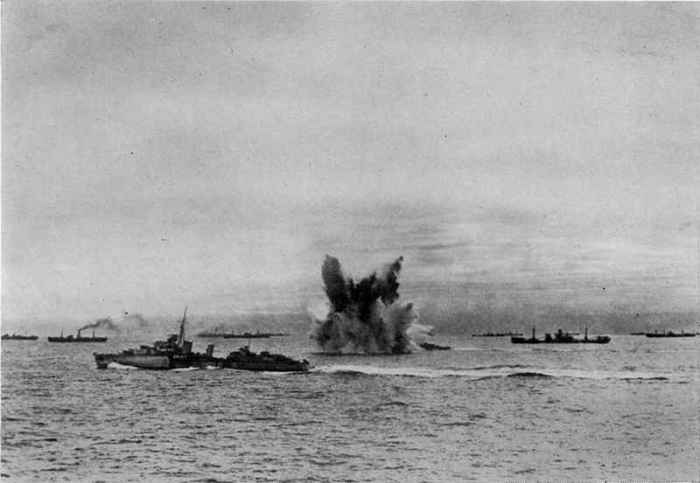

A German supply ship is being torpedoed by IROQUOIS in Audierne Bay, close to Brest on 23 August 1944. This followed a night of action which saw an enemy convoy destroyed by a force consisting of HMS Mauritius, HMS Ursa and Iroquois. The photo was taken by Roy Kemp a Toronto Daily Star reporter who was on board at the time.

The enemy could come out the sky anytime. Iroquois’ anti-aircraft crews were ever vigilant against attack. This twin barrel, 20 mm Oerlikon weapon was commonly used against aircraft. (Photo courtesy Tom Ingham)