Clarence Simonsen sent me this message with a request…

What I am attempting to do is to show aviation people that I have a passion for my research and the veterans. I always attempt to speak the truth and tell a new story. This was all done as a lead up to the next large story.While this true history is long, I have only sent you about one-third of the history I have, and it is an attempt to get some action from Ottawa.

The lead in history is very important and I have worked on this for the past 37 years, and can’t get anyone to listen. I have approached people ask for their help to create a nose art museum to honor the WWII forgotten RCAF members who painted nose art.

Silence…

I phoned and spoke to someone after the 2011 story came out in Ottawa Citizen newspaper on the wrong veteran pilot who flew Willie the Wolf, and I explained everything over one-hour. That is when I received his reply – “We have to watch what we do and say, in regards to Canadian Government, active squadrons and Ottawa museum’s, as we work closely with them.”Here is the message I wish to get out ……

In 1999, the American White House Millennium Council set the seeds for the protection of all threatened cultural treasures. This included the original and largest collection of WWII nose art cut from the American B-24’s and B-17’s being scrapped in 1947. This collection of 33 panels, 11 cut from the B-17 and 22 cut from the B-24 bombers, served with five American Air Forces in WWII. Thirty-one of the panels contain the image of the female form, and twelve are in fact full nudes. These 33 panels were painted on bare [no primer paint] aircraft skin and the paint was chipping. Each panel had to be saved at a cost per panel of $20,000 US bucks.On 5 October 2002, the world’s largest nose art galley opened in Midland, Texas. This museum records the identity of all the ground and flight crews involved with each nose art aircraft, the meaning behind the aircraft nose art, and most of all the history of the nose artist who pained each aircraft. I was involved in a small part, another story.

We, [Canadian taxpayer] own the second largest nose art collection in the world and it has been neglected for the past 70 years. Thanks to you, I can now tell the true story, and that is all I have left. The world war two bomber which most Canadians flew and died in is the Halifax British built four-engine aircraft, and that can never change. The art or name painted on the Halifax bomber helped fill a mix of psychological needs in WWII, some was to defy military authority, others to show crew success, to bring good-luck, and soon it became a huge Air Force morale builder.To see a true Halifax B. [combat] bomber you have to go to the Yorkshire Museum in England and see “Friday the 13th” which is the complex composite build from original parts. The RCAF Halifax in Trenton is a British Mk. “A” transport aircraft, not combat. to see the original RCAF Halifax nose art panels you have to go to the War Museum in Ottawa, but they contain no history. To understand the history you must go to my 37 years research page on the website at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada at Nanton, Alberta.

Can you please tell the simple fact: Canadians need a museum [like the Americans] to display and record our WWII nose art history.

Clarence

Ottawa, we have a problem

This is a text version…

“Houston, we have a problem”

The most famous misquotation in the world today, used to report any kind of major problem. Thanks again to Hollywood, USA, the original dialogue was edited from the genuine life-threatening report, in the same way they create and edit their own American film events of WWII.

14 April 1970, Apollo 13 is on her way to the moon and “Bang.” John Swigert to their base in Houston, ‘Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.’ This however is never used and the misquote is world famous, as it gets directly to the point. In 2001, when Whitney Houston died from health and drug addiction problems, everyone knew she had a problem, but …., it became world famous again. I now wish to use the misquote as my title to draw attention to this WWII Canadian dilemma ——-

“Ottawa, we have a problem.”

In 1977, I was deeply involved with the WWII aircraft nose art used by the American Mighty 8th Air Force in England. This led directly to my very first visit to the old War Museum and the RCAF archives on Canadian WWII nose art. First, you must process a great deal of patience to do anything in Ottawa, which I soon found included my nose art research. It was unknown to everyone I approached, and four out of five Government employees just didn’t care. Then fate stepped in to help me, and to this day, I can’t say enough good things about a lady named Mrs. Janet Lacroix. Janet worked for the Department of National Defence, Canadian Forces Joint Imagery Centre, Building M23, Montreal Road Campus, Ottawa. She loved her job and was an expert on the location of WWII negative images, [which were in different locations] including nose art. Janet understood my nose art research was about saving RCAF history, and it was my passion, with no support or funding. At the time I was a police officer in Toronto, and in my days off I would drive to Ottawa, rent a hotel, and spend two or three days going over files, etc. I never ask Janet to help me, but over the next 40 years she would search out material that I was seeking and mail it to me or make letter contact if money was involved. A part of the following RCAF history was found and saved by Janet Lacroix, and for that, I owe her many thanks. In fact the “War Museum” in Ottawa owes her thanks, but they have no idea.

The first Handley-Page Halifax prototype bomber flew on 25 October 1939, just after the start of WWII. A grand total of 6,178 four-engine Halifax heavy bombers were built in England during the war 1939-45. At peak production, which was reached in the summer of 1944, 41 British factories and 600 sub-contractors, with 51,000 employees, produced one huge Halifax every hour. As soon as they entered service with RAF and RCAF squadrons, a large number were shot down, and only four survived to reach the century club mark of over “100” operations. Thousands of young men in Bomber Command climbed into their Halifax and took off, never to be seen again. They spent six to eight hours in their metal flying machine, which for many became their casket. In the past fifty years, I have interviewed over one thousand of the air force survivors and it is only after listening to these veterans, that the true dangers of the air wars become apparent.

During the Second World War the Royal Air Force Bomber Command lost a total of 55,358 personnel, on active bombing flying operations. This included 8,240 RCAF aircrews killed on active bombing operations, and most were killed in the Halifax bomber. No. 6 [RCAF] Group flew 40,822 operations in WWII, with 73% [28,126] flown in Halifax bomber aircraft. No. 6 [RCAF] Group lost 814 bomber aircraft over enemy territory, 127 were Wellington bombers, 149 were Lancaster bombers and 508 were Halifax bombers. Many of these aircraft carried the most and best of the “Canadian” painted nose art images, and now only a few black and white photos remain.

With the end of the war in Europe [8 May 1945], the British Government ordered 1,376 surplus Halifax bombers to be cut up and scrapped in England. These included the combat veterans of WWII, many containing nose art, which were flown to a storage maintenance unit for the last time and parked. The following records tell the real story – Halifax Mk. II, 114, Mk. III, 533, Mk. V, 164, Mk. VI, 391, Mk. VII, 103, Mk. VIII, 54, and Mk. VIX 17. In just seven short months [January 1946] only 198 Halifax bombers remained to be scrapped. The destruction was complete along with their WWII nose art.

The majority of the “Canadian” RCAF Halifax aircraft [Mk. III, Mk. V, and Mk. VII] were ferried to two large ‘graveyards’ in England. The largest number of RCAF bombers was stored at No. 43 Group, the former Handley-Page Halifax repair depot at Rawcliffe, Yorkshire. This grass landing strip [with club house] was first constructed near the village of Rawcliffe, at Clifton in 1935. In September 1939, when war was declared, the British Air Ministry took charge of the aerodrome and assigned it to RAF Station Linton-on-Ouse. In the spring of 1940, the RAF erected many wooden huts and buildings around the old club-house, situated near the south-east corner of the field. In 1941, a small wartime RAF airfield was constructed on the property with facilities for 500 airmen.

Due to the large number of Halifax four-engine aircraft based in Yorkshire [All 6 Group RCAF], the British Air Ministry of Aircraft Production decided to establish a civilian run repair unit [C.R.U.] at Clifton beginning in late July 1941. Three large concrete runways were constructed with a perimeter track, and 12 new buildings were added including new hangers and flight huts, all dispersed around the perimeter track. The new site was called No. 135 Halifax Repair Depot, Clifton, Yorkshire. In 1942, two large hanger complexes were built, one on the Rawcliffe side and one on the south end called Water Lane. During the remainder of the war over 2,000 Halifax aircraft [including all the Canadian 6 Group] were repaired or overhauled by a very large civilian staff of mechanics and engineers. In mid-May 1945, the British Air Ministry turned Clifton into a massive graveyard for storage and scrapping of the Halifax bombers and named it No. 43 Group.

A second site was selected by the Air Ministry [for storage area] and named No. 41 Group, which had been the former No. 48 Maintenance Unit, located at High Ercall, Shropshire, containing one of the largest airfields in England. With the end of the war in Europe, this site was selected for the storage and scrapping of the remainder of the Canadian No. 6 [RCAF] Group Halifax bomber aircraft.

Canadian Officer F/L Harold H. Lindsay, RCAF Operations Officer stationed at High Wicombe, RAF Bomber Command, suddenly realized that all of the Canadian Halifax nose art painted during WWII would be lost with the scrapping of the British built bombers. It was extremely important that some of the best looking nose art painted on the British Halifax bomber be saved for historical merit, and shipped to Canada. This single RCAF Officer took it upon himself to save this soon to be scrapped nose art form and approached Wing Commander W. R. Thompson, [A.O.C. of RCAF Operations Overseas] who in turn granted approval to do what he could to save the aircraft art.

F/L Lindsay first decided to record all of the Halifax aircraft nose art in black and white 35 mm film, and then he would select a number of the best to be cut from the bomber nose, crated and shipped to Canada. Lindsay arrived at No. 41 Group High Ercall, in a small British truck driven by a Mr. Robert Goodwin, an employee of the scrapping operation.

The date is unknown, but this is F/L Harold Lindsay standing under RCAF Halifax Mk. III, serial MZ655, that flew with No. 431 Iroquois Squadron during WWII. Found by Janet Lacroix

This deserted airfield contains the survivors of the veteran Halifax bombers that flew in WWII, and almost each one has a painted nose art image, containing operations with bombs, crew names, and most of them have flown with No. 6 [RCAF] Group. They are now standing alone, silent in the spring wind, wing tip to wing tip, no roar of engines, no dripping oil and no bombs to carry, the conflict is over. In a few short weeks they will be reduced to cut up sections, scrapped for pots and pans, and then forgotten. Lindsay is here to save what he can in photos and mark others for return to Canada.

This is Robert Goodwin, under the same Halifax serial MZ655. After a photo is taken, Lindsay will mark a nose art for removal, and later Goodwin will cut the nose art from the RCAF bomber, crate and ship to Canada. (Found by Janet Lacroix)

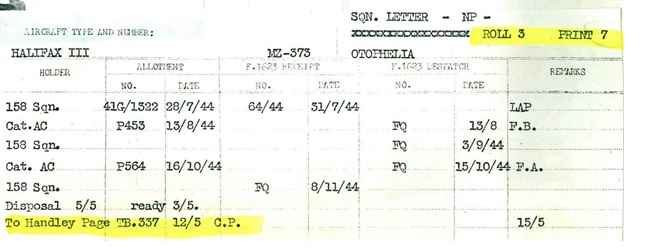

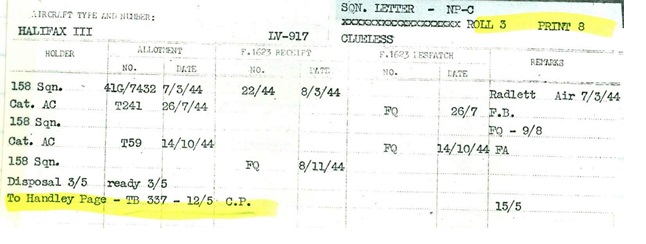

Like all war time RCAF Officers, F/L Lindsay records everything on file cards, which are shipped to Canada [1946] with the original nose art panels.

Each file card has a 35 mm negative number and all begin with RE77-?? This should be very simple to record, but it is not. Beginning in 1977, I attempted to place the file cards and negative numbers together and found that a good number were in fact missing from the Canadian Forces Joint Imagery Centre in Ottawa. In the following twenty years Janet Lacroix located a few missing negatives and file cards, which had been borrowed by the Canadian Aviation Museum and the War Museum and never returned.

Today [2014] some of the missing negatives and files are still gone, and I hope only misplaced. The fact remains – “How can Ottawa teach to the future generation, if we have forgotten and lost our RCAF past?

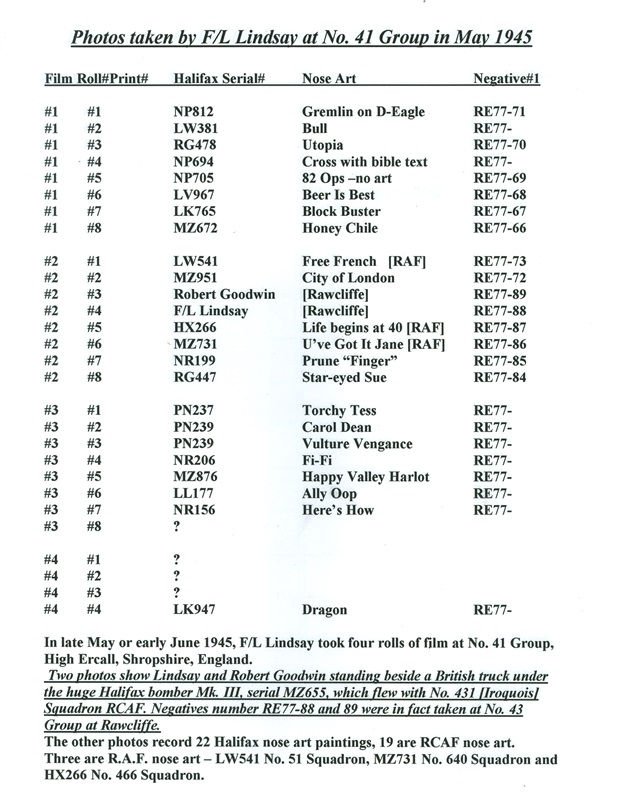

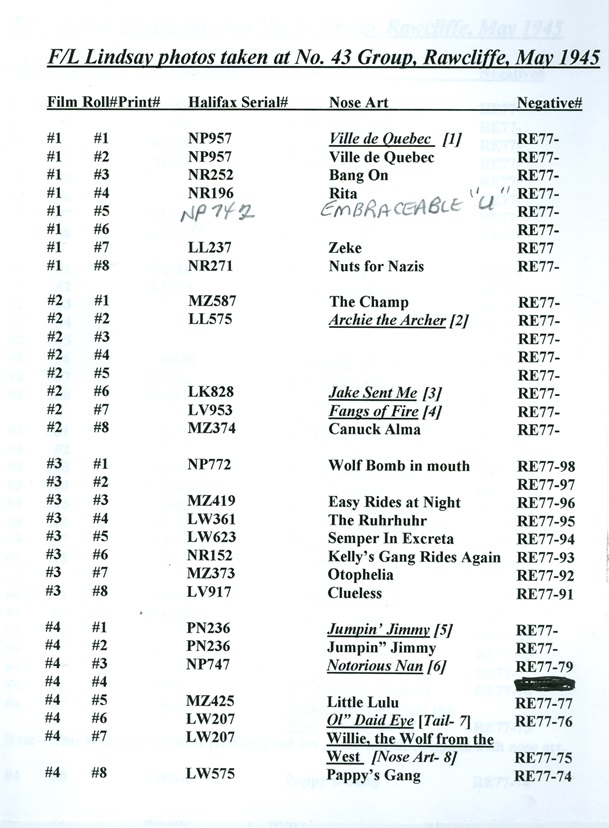

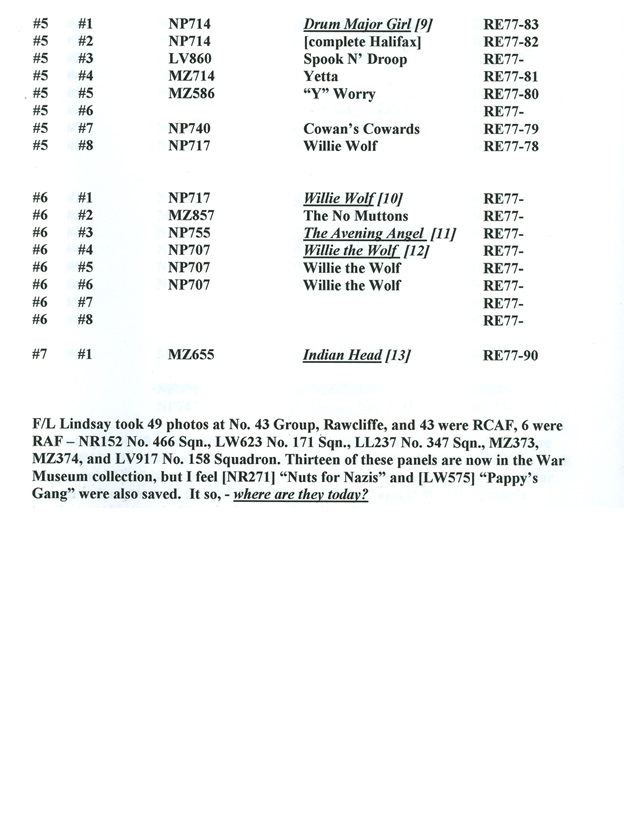

From the known info, I have placed together the record of photos taken by F/L Lindsay in early May 1945. He took four rolls of 35 mm film B & W, containing eight prints per roll. The total photos in Ottawa [I found] that were taken at High Ercall, in 1945 are 22 nose art images, 19 are RCAF and three are RAF. Thirteen 35 mm negatives with RE-77?? numbers are missing.

Here are selections from my research which began in 1977 at Ottawa. During the past fifty years, I have continued to conduct interviews, record photo images, and learn the truth of what Lindsay did in May and June 1945.

Here is the very first photo taken by F/L Lindsay at No. 41 Group High Ercall, Shropshire, in early May 1945.

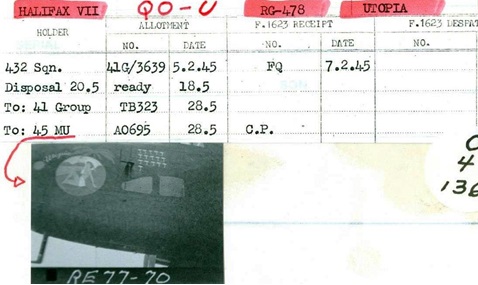

and his file card for this Halifax bomber.

This impressive RCAF nose art was not saved and was scrapped on 29 May 1945.

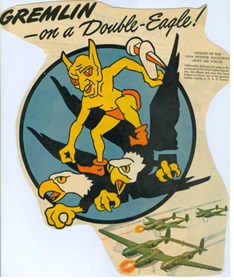

This was the second Halifax bomber to wear this nose art in No. 432 [Leaside] Squadron during WWII. The first “Gremlin On A Double Eagle” appeared on Halifax Mk. III, serial MZ582, code QO-Z, with name “Zombie.” This RCAF Halifax bomber flew with No. 432 Squadron from February to July 1944, completing 34 operations. On 29 September 1944, a new Halifax Mk. VII, [above] serial NP812, bomber arrived with Leaside squadron and it received the same style “Gremlin” nose art. This new bomber flew 21 operations until 20 March 1945, when it was sent to No. 41 Group High Ercall, on 20 March 1945. In mid- May F/L Lindsay came to High Ercall and took the last photo of “Gremlin on Double Eagle.” It was soon scrapped.

The original old bomber Halifax serial MZ582, was transferred to No. 415 [Swordfish] squadron and survived the war. This aircraft and nose art was also scrapped in England.

This wall art mural was painted on a Mess Hall building at East Moor, Yorkshire, during WWII and remained until 1981. It is the same image of “Gremlin on Double Eagle” that appeared on two Halifax bombers in No. 432 Squadron, from the same air crew that ate in this very building.

Unfortunately aviation historians cannot ignore the simple fact the thoughts and general information of a large percentage of wartime Canadians was molded through the medium of American radio, Hollywood films, and most of all reading material. [It’s still going on] As Canada entered WWII, it became a logical conclusion that a great percentage of nose art ideas and paintings came from American publications. This unofficial USAAF insignia was created for the 339th Fighter Squadron and appeared in a 1944 issue of LIFE magazine.

In May 1945, F/L Lindsay went to great lengths to save and preserved the WWII Halifax RCAF nose art original panels and photo images. They still remain on a wall in the War Museum Ottawa, but contain no history or teaching guide for future generations to learn and respect. In 2007, I was contacted by Mr. Don Smith who was designing the new Air Force Museum located in the Military Museum’s of Calgary. Don must tell the complete history of Canada’s Air Force but he only processed one original aircraft. I was ask to help and in the replica Nissan Hut, I created the “Gremlin on Double Eagle” complete with nose art history. This is a very simple way to use a RCAF nose art image and educate all ages of school children who pass through the door’s of Calgary’s Military Museum’s. You must understand the RCAF heroes of WWII were average age 17-24 years, that’s why this art impressed them, and it has the same effect on today’s youth.

Now let’s follow in the footsteps of F/L Lindsay in May 1945 and the third photo he snapped.

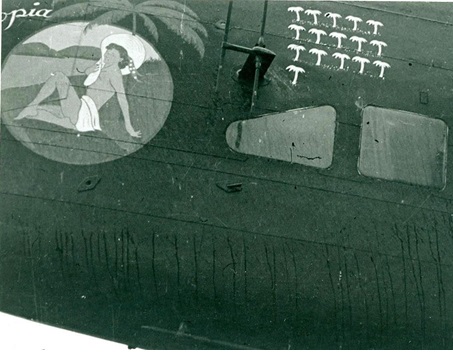

He snaps roll #1 image #3 Halifax serial RG478 “Utopia” with palm trees for operations.

Scrapped!

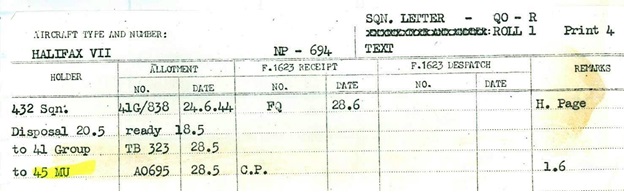

Next he takes roll #1, image #4 Halifax, serial NP694. This was painted by LAC Thomas Dunn, who I interviewed in 1991, and along with this photo is another image showing the first painting without art work. A wonderful history to a proud veteran RCAF bomber that flew 78 operations.

Scrapped!

The original file card Lindsay completed for the Bible Text nose art.

This is snapped on roll #1, image #6, a simple photo showing a line of RCAF Halifax aircraft ready to be scrapped.

Scrapped!

The nose art has been painted over with black paint and Lindsay records on his file card “Beer” but that is all he can make out. Halifax Mk. III, serial LV967, and that is it. I have interviewed one of the original ground crew members and this bomber flew with No. 433 and No. 429 RCAF squadrons, completing 68 operations and her nose art name was “Beer is Best.” This is the last you will ever see of her, thanks to F/L Lindsay.

Photo Victor Swimmings, ground crew second from left.

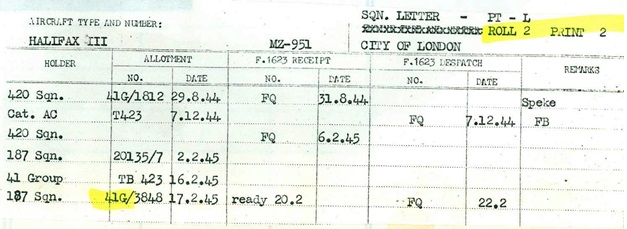

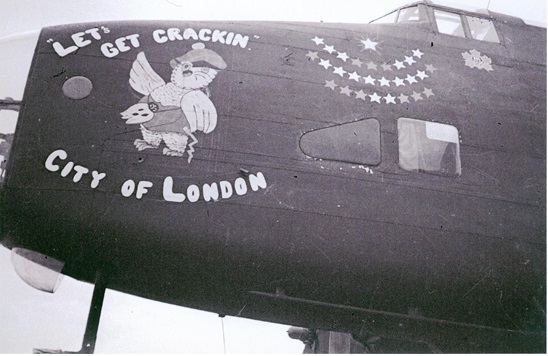

This is the file card completed by F/L Lindsay in possibly June 1945. This RCAF Halifax had been transferred to RAF No. 187 Squadron on 2 February 1945, then went to No. 41 Group [High Ercall] on 16 Feb. 45, for scrapping. It was ready for scrapping on 20 Feb. 1945, but still remained parked on the field grass when Lindsay arrived in early May 45, to record the image which he noted as Roll 2 Print 2. City of London was –

Scrapped!

Roll #2, print #2 as seen by the eye of F/L Lindsay, which has been sitting in Ottawa since 1946.

These images along with the history need to be displayed by our Government, in a special museum like the Americans do. How about the “Vintage Wings of Canada Nose Art Museum?” or the “Shell Canada Nose Art Museum?” NHL teams make bags of money to allow their home rink to carry a name, why not our RCAF Museums?

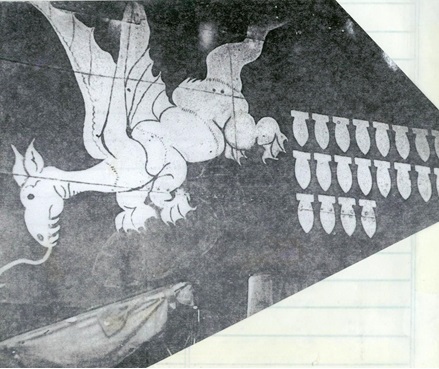

The Flying Dragon is the last photo taken by Lindsay at No. 41 Group High Ercall, Shropshire and this will become the only nose art selected for shipment to Canada. Film roll #4, print #4 “Dragon” serial LK947.

This “Flying Dragon” Halifax serial LK947 arrived new with RCAF No. 428 [Ghost] Squadron on 15 October 1943, where she completed eight operations.

On 1 February 44, she was transferred to No. 429 [Bison] Squadron, flying only four operations. Then transferred to No. 434 [Bluenose] Squadron on 4 March 44, coded SE-Y and after seven operations is sent to No. 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit for training, which began on 16 May 1944. For the last time she is transferred to No. 1669 H.C. U. on 19 October 1944. On 9 February 1945, she is flown to No. 41 Group, High Ercall, where Lindsay takes her photo three months later. This is the only nose art from No. 41 Group which was selected and shipped to Canada in July 1946. Today it is the War Museum collection, without a history.

A total of nineteen RCAF aircrews flew in this bomber during her 24 operations, beginning on 22 October 1943 when the crew of F/Sgt. E. O’Connor took her to bomb Kassel, Germany. This crew flew her three more times. On 19/20 February 1944, the crew of pilot/Sgt. E. L. Howland from USA, took her to bomb Leipzig. This same crew will be shot down by flak over Dusseldorf while flying Halifax LV963 on 23 April 1944. Five are killed including American pilot Howland. The last crew to fly her on operations is F/Sgt. W. Wood, and his crew on 7 May 1944, to bomb Frisian Islands. The bomber is then transferred to No. 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit on 8 May 44, to train new members of the RCAF.

This is the type of history we need with the original nose art panels in Ottawa.

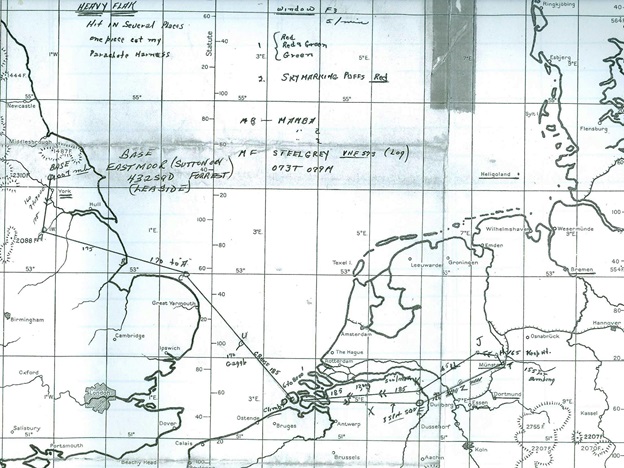

F/L Lindsay and civilian Goodwin will now drive over to No. 43 Group at [Rawcliffe] Clifton, Yorkshire and record the nose art on these RCAF Halifax aircraft. [I believe the date was 8 to 16 June 45].

Lindsay will take 49 photos and 43 are ex-RCAF bombers. He will select thirteen of these nose art paintings to be cut and shipped to Canada. Robert Goodwin will later cut these nose art panels from the bombers, crate each one and place on a ship for Canada. They arrived in Ottawa on 7 May 1946 almost a year to the date Lindsay began his salvage mission. He has saved the second largest collection of original WWII nose art in the world, and preserved RCAF huge amount of Canadian aviation history. Nobody cares.

For the next 60 years, only four of these original panels will be seen, and that will be for the eyes of only Air Force officers. On 8 May 2005, the fourteen original Halifax panels will at last go on public display in the new War Museum, however they contain no history and contain no learning for future generations of Canadians.

This is how Lindsay saved our Canadian original nose art collection.

The true story of the F/L Lindsay collection is still stored someplace in Ottawa today. However, it seems nobody cares, other than me. I have turned 70 years of age and have no funding to complete by 50 years of RCAF nose art research. The following is what I believe occurred at Rawcliffe, in early June 1945. I believe it was in an eight day period from 8 June to 16 June 1945.

The scrapping at ex-No. 135 [C.R.U.] Civilian Repair Unit, Clifton, York, began as soon as the war in Europe ended, mid-May 1945. Records show 1,376 Halifax bombers were scrapped and this included the most and best RCAF veteran aircraft. The photos show that when Lindsay and Goodwin arrived at Clifton, the wings, engines and tails had been cut from many of the Canadian RCAF Halifax bombers. At once Lindsay realized he would have to move fast to save this WWII RCAF aircraft history and nose art paintings. For that reason, he photographed and selected the thirteen [numbered above] panels that are in Ottawa today.

The people living in the village of Clifton, reported they could see the mountain of cut up Halifax aircraft, which reached 80 feet in height in just four short months.

Warning – the next photos are not easy to look at, as they are in fact the graveyards of our proud WWII RCAF Halifax history.

This is a photo-copy obtained in 1977, for the simple reason the original Ottawa negative could not be found.

Please note – the wings and tails have been cut off these once proud RCAF birds and they are in fact Penguins. This is the image Lindsay saw as he clicked his camera. He went from Halifax airframe to airframe, recording the image and marking to return to Canada. He had to hurry, as very soon the fuselage and nose art would be cut-up, and history would be lost forever. This is roll # 1, print #1, negative number unknown and missing.

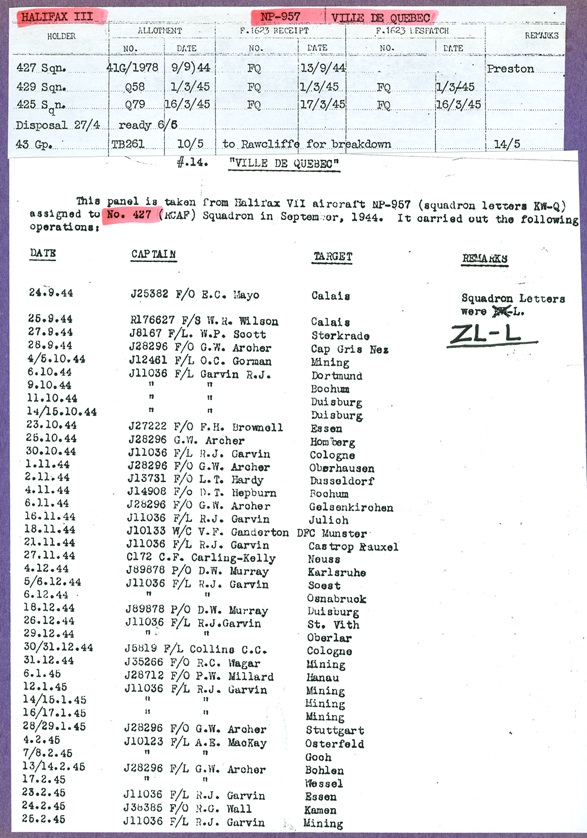

While the original nose art painting in Ottawa shows this to be a No. 425 French-Canadian squadron with Quebec nose art, the correct history is obtained on the Lindsay record card and operations flown.

The Halifax flew with three RCAF squadrons and only completed ten operations with 425 Squadron and thus the nose art was painted very late in the war. It is clear to see that this info is required by the War Museum collection to form any correct part in the aircraft history, or just our Canadian history in general. Today the history of No. 427 and 429 Squadrons are totally lost, while the nose artist and his French-Canadian history are also forgotten. This is no way to run a world class Museum.

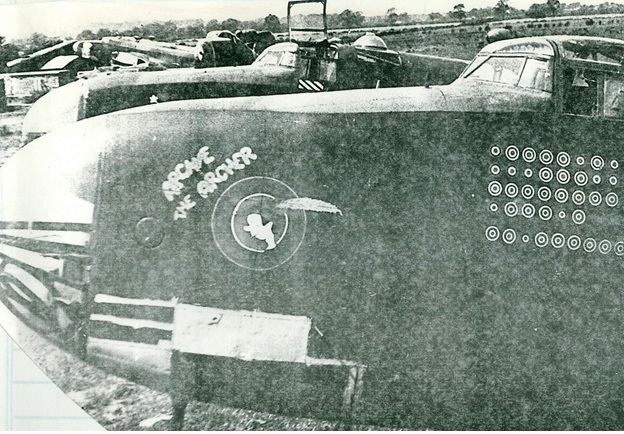

This is what Lindsay saw as he took roll #2, print #2, ‘Archie the Archer’ serial LL575, saved and today in the Ottawa collection. Again, the wing-less birds of the RCAF stand in line awaiting their fate.

This photo was taken at No. 1664 Heavy Conversion School, the finishing school for aircrews located at Croft, between 10 December 44 to 13 April 1945. The bomber would be flown from Croft on 15 May 1945 to No. 43 Group, her last stop. Lindsay would arrive about three weeks later and take the last photo, then scrap.

This was photo roll #1, print #3 Halifax “Bang On” flew with No. 425 Squadron but the nose art was not saved.

In the far background is another 425 squadron Halifax that appears in roll #1, print #8 and it is named “Nuts for Nazis”.

This is the 1977, photo-copy I obtained in Ottawa due to the fact this original negative RE-77?? is also missing. When I discovered this nose art is not in the Ottawa collection, I can’t believe it. I know that Lindsay would save this outstanding nose art. You be the judge. I believe it was stolen in 1946.

I spent many years doing research on this Halifax bomber and you can find the complete history on Bomber Command Museum of Canada, at Nanton, Alberta, website for 2007.

I have painted this Nuts for Nazis replica four times, beginning with far right, painted for Smithsonian lecture given on 18 July 2004. This was presented to Betsy Platt at the Ripley Center, 1100 Jefferson Drive, Washington, D.C., in tribute to the 704 Americans killed in action wearing the uniform of the Royal Canadian Air Force in WWII.

The image on left was taken by F/L Lindsay at No. 43 Group in May 45. The photo on right came from Richard Koval and this is the nose artist, rear-gunner Sgt. Fred Henry King. He also appears above painting the nose art. The Halifax Mk. III, serial NR271 was received new on 23 November 1944, receiving the code letters KW-N in No. 425 Squadron. It was flown twice by other crews – 4/5 December 44 to Karlsruhe, and 5/6 December to Soest. On 6/7 December 44 it was first flown by F/Lt. Charles Lesesne C3879 [French-American] and crew to Osnabruck, Germany. They will fly “their” Halifax on 18 more operations, until Easter 31 March 1945. On that fateful day, they are assigned to fly Halifax MZ418 and not “Nuts for Nazis” in a major daylight raid on Hamburg. The Luftwaffe launch a surprise attack of some forty Me262 jets, which was the largest force of the jets sent into combat, during WWII. No. 6 RCAF Group was attacked by thirty Me262 jets and lost five Lancaster Mk. X’s and three Halifax aircraft including MZ418 flown by American Lesesne. The crew jump and survive, pilot Lesesne is taken prisoner, beaten to near-death by German women and then thrown in the local police cells, where he is left to bleed to death. Nuts for Nazis, Halifax NR271, continues to fly operations with other French/Canadian crews, completing seven until the 25 April 1945. It is flown to No. 43 Group on 10 May 1945 for scrapping. F/L Lindsay records two photos of this bomber, roll #1, print #8, which is the last in that camera roll. He then takes a second photo of the nose art [above left] but that negative is missing in Ottawa.

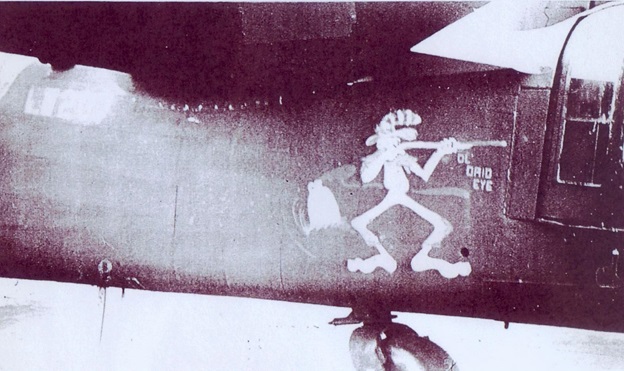

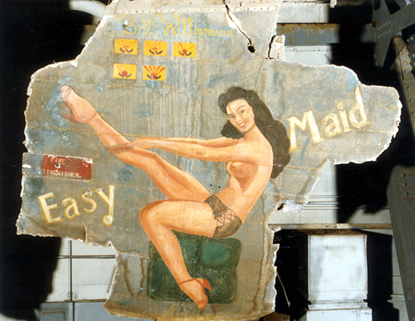

The rarest and most valuable aircraft War Museum art work is in fact not even nose art, but tail art. The only original WWII tail art in the complete world and the War Museum have no history.

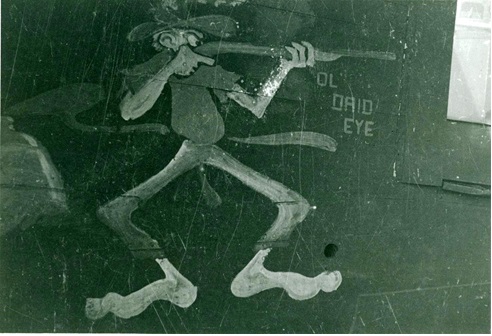

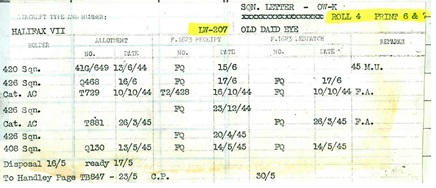

On roll # 4, print # 6 Lindsay records the following Halifax tail art called – “Ol’ Daid Eye”, serial LW207.

On the very next photo he records the nose art with a “Wolf” head and no name, serial LW207. This is from one single Halifax bomber, the only nose and tail art in the world, truly amazing WWII RCAF bomber history.

Want to build a rare WWII aircraft that’s not German or American. OK, then construct this rare Canadian flown RCAF Halifax, which has nose art and tail art, and both originals can be seen today at the War Museum in Ottawa.

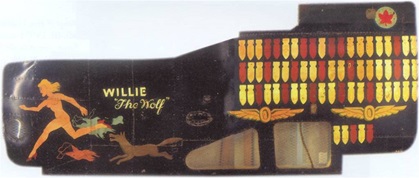

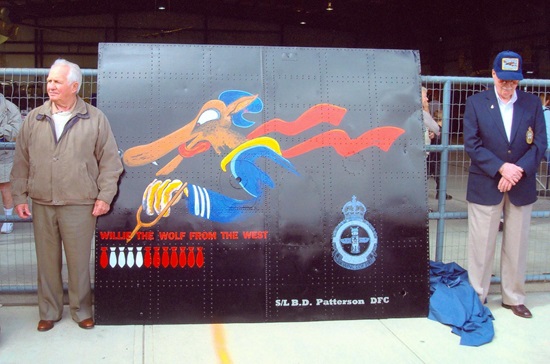

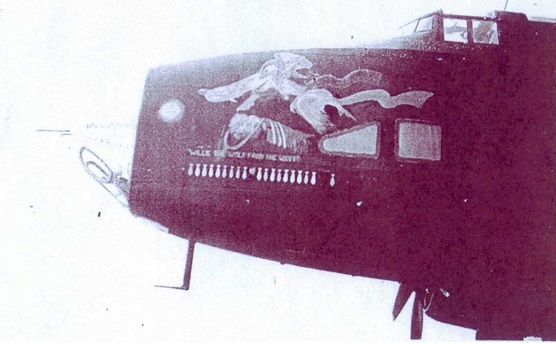

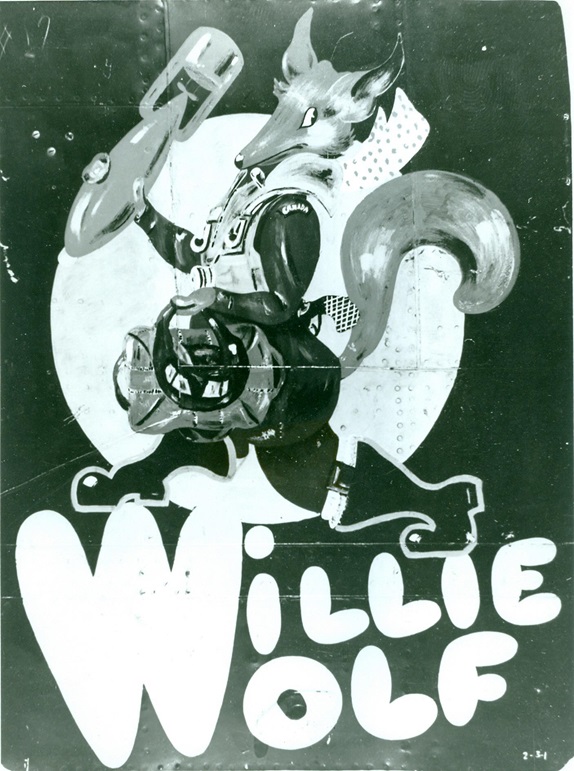

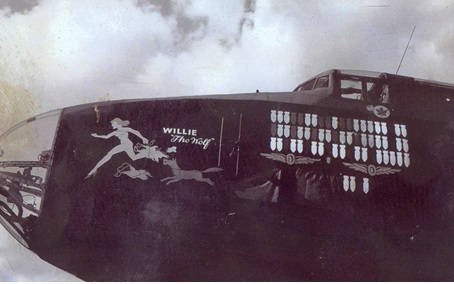

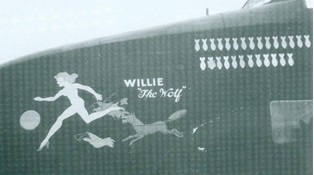

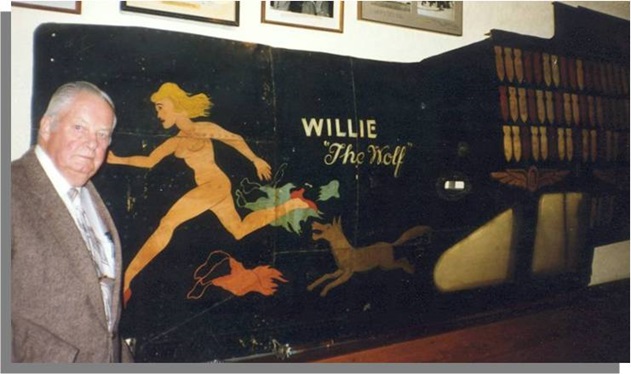

This nose art story begins on a Halifax production line and a new batch started 13 May 1944. Two days later Halifax Mk. III, serial MZ674 is delivered to No. 426 [Thunderbird] Squadron of the RCAF and flies her first operation on 17 May 44. The aircraft has received the code letters OW-W and is flown on a number of operations by the Officer Commanding “B” flight, S/L B.D. Patterson from Calgary, Alberta. His log book shows he flew Halifax MZ674 on eleven dates, [beginning 17 May 44] which included seven operations, the last to Boulogne on 15 June 1944. During this period of time he had nose art of a Wolf painted on this Halifax, with words “Willie the Wolf from the West” [Calgary].

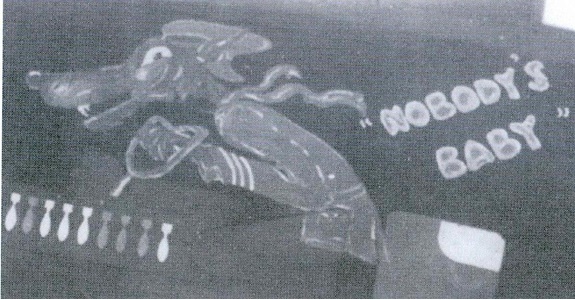

In mid-June 1944, No. 426 Squadron begin to re-equip with new Halifax Mk. VII aircraft, and serial MZ674 is transferred to No. 425 [Alouette] French-Canadian Squadron on 16 June 44.

The original S/L Patterson nose art of Wolf remains, however the new 425 crew give her a new name “Nobody’s Baby”.

S/L Patterson in 426 Squadron receives a new Halifax Mk. VII, with code letters OW-W, serial LW207. On 23 June 44, he flies her for the first time to bomb Bientque, France. At some date he asks the squadron nose artist to repaint the same “Willie the Wolf from the West” on his new Halifax. He is pilot of his Halifax a total of seven times, the last on 10 August 1944, to La Pallice.

The nose art idea came in part from an 11 November 1943, film release of “Riding High”, staring Dorothy Lamour with a hilarious song by Cass Daley. The song had the title – “Willie the Wolf of the West” and this was changed to read ‘from’ in reference to Patterson’s birth city, Calgary, Alberta. Again the effect of American Hollywood movies had a major impact on RCAF nose art.

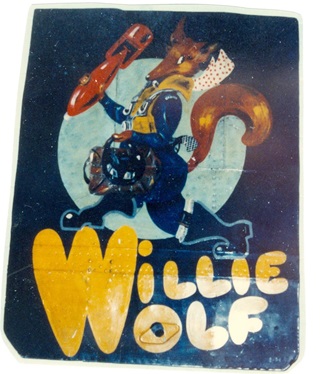

The nose art also came from wartime effect on life, death and separation from Canada. The members of the Royal Air Force, Royal Canadian Air Force and American 8th Air Force, suffered the highest causality rate flying in the air over Europe during WWII. This fear of death provided a powerful incentive to make love at every opportunity while on leave in England. With so many aircrews seeking a romantic adventure, the British ladies stated they were stalked like a pack of wolves, and the term stuck. In January 1942, an American soldier began a cartoon series based on this very idea. A serviceman in Army, Navy, or Air Force, uniform was drawn with a wolf head. Each cartoon featured a sexy lady and a play on words, relating to sex. The Wolf was named “Willie”, thus it appeared on hundreds of aircraft, three of which are in Ottawa collection today.

“Willie Wolf” NP717, “Willie the Wolf” NP707 and “Willie the Wolf from the West” LW201.

This photo dated 29 August 44, shows the impressive nose art of “Willie the Wolf from the West” as her pilot S/L Bedford Donald Chase Patterson speaks with his ground crew, [left] is LAC Jake Shantz, and right Don Forster. This print has been signed for Clarence Simonsen by the rear and mid-upper Gunner who flew in LW207, P/O William Francis Bessent J88434, DFM. [That is special as you read later]

Halifax LW207 completes 41 operations until 10 October 1944, and then is damaged in a taxing accident. Repairs are completed on 28 February 1945, and the Halifax receives new code letters OW-K. The Halifax survives the war flying 58 operations. On 14 May 1945, the Halifax is transferred to No. 408 [Goose] Squadron.

For some unknown reason the ground crew of No. 408 Squadron paint over most of the original nose art leaving only a Wolf head. They also paint over the name and add extra bombs on the nose. The bomber never flies operations with No. 408 and is declared ready for disposal on 17 May 45. It is then flown to No. 43 Group at Rawcliffe, 30 May 45 where it is photographed by Lindsay, roll # 4, print # 7.

It is clear to see where the 408 squadron painted over the Wolf body, hand on aircraft control and full name. Over the name they painted 14 white bombs. The next two rows of bombs were the original operations flown by 426 Squadron, which total 53, five short of her grand total of 58 operations. This is the panel [wolf head only] that Lindsay marked for Canada and today is in the War Museum. Without this history the Wolf Head means nothing, and students learn nothing.

This is a replica of the original nose art on Halifax VII, serial LW207, painted on Lancaster wing panel for Bomber Command Museum at Nanton, Alberta.

The man on the right is W/C C.M. Black DFC, Commanding Officer of No 426 Thunderbird Squadron from 29 Jan. 45 to 24 May 45.

The man on the left is P/O W. F. Bessent, DFM, the rear and mid-upper gunner in this very aircraft. [Author collection and nose artist]

This photo is from P/O Bill Bessent collection.

From Bill Bessent collection, showing the position he flew in most, [rear gun] and the serial of LW207.

While these images are not clear it gives a good view for model builders showing correct position of rare tail art. These have never been published before. Enjoy.

This is from the author collection, taken at No. 408 Helicopter Squadron, Edmonton in 1986. [Free to use for models]

The rare tail art inspiration came from this wartime American Hill-Billy ad.

This photo from Ottawa [PL40133] caused many problems for not only the War Museum but also historians seeking the truth.

P/O C. L. Humphreys was the rear gunner with the crew of pilot P/O T.V. Barger #J86279, who flew twelve operations in No. 408 Halifax serial NP717 with name “Willie Wolf”. This panel was saved and today is in the collection in the War Museum. Gunner Humphreys never flew in Halifax LW207, nose art “Willie the Wolf from the West” and tail art Ol’ Daid Eye”, he only had his photo taken by the rear turret after 13 May 1945. Halifax LW207 was transferred from No. 426 squadron to No. 408 Squadron on 13 May 1945.

This is the Halifax serial NP717 that P/O Humphreys flew as rear gunner [twelve operations] from 7 August 1944 until 25 October 1944, named “Willie Wolf.”

This image was taken at No. 408 Tactical Helicopter Squadron, Edmonton, in 1986. – author collection.

This is the image taken by F/L Lindsay at No. 43 Group, Rawcliife, in mid-June 1945, on roll #6, print #1. Halifax serial NP717, “Willie Wolf” arrived at No. 43 Group on 2 May 45, and was scrapped on 24 May 45. This nose art is in the War Museum collection today. Now you know part of the correct history which should be displayed with this original panel in Ottawa.

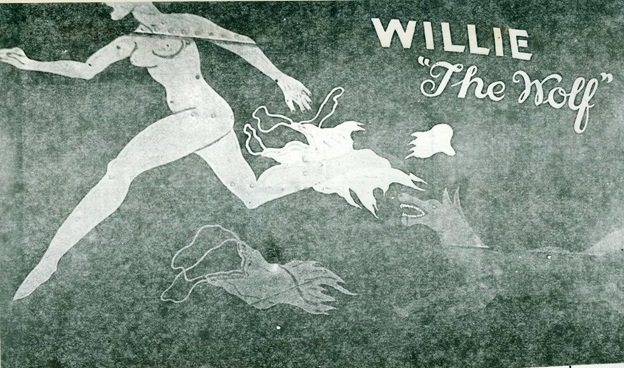

Lindsay records the next Halifax, MZ857, named “The No Nuttins” No. 433 squadron as roll #6, print #2 and moved on to record Halifax NP755, “The Avenging Angel” No. 432 squadron, which is a full nude lady roll #6, print #3. Today this is in the collection but she is wearing a green bathing suit. Next in line is “Willie the Wolf.”

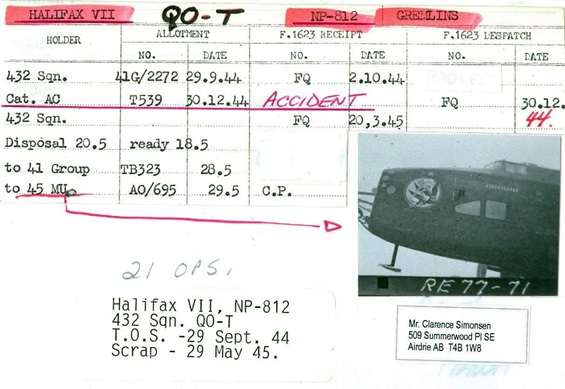

F/L Lindsay approaches the next Halifax serial NP707 and he was instantly impressed with the grand scale and bomb total recorded beside the nude lady running from a Wolf. This is the only time he took three photos of one single bomber, which are on roll #6, prints #4-#5-#6. The negative numbers are not known due to the fact they cannot be found. This is a 1977, photocopy image taken from the photo on file in Ottawa.

[Harold Kearl collection] – This image was recorded on 10 April 45, after F/O A. R Nicholson J41957 had flown Willie to Leipzig, Germany, her 63rd Op.

This should be the centre attraction for the nose art collection in the War Museum, but it is not, and in fact it continues to be confused with the same style nose art that appeared on a Halifax in No. 415 Squadron.

Two years ago, just before Nov. 11th, a nose art story appeared in the “Ottawa Citizen” newspaper and the pilot was from Ottawa flying with No. 415 Squadron during WWII. He stood very proud and told how he flew this very nose art, on his Halifax during WWII. That was false, so I e-mailed the senior reporter who wrote the story for the Ottawa Citizen newspaper, and explained his mistake. His reply was – “Well, Clarence, we can’t embarrass an RCAF veteran can we.” No, we can’t, and I shut up, however this clearly again shows the problems with our display of RCAF history in the War Museum. If the Ottawa press can’t get it correct for a “Remembrance Day” story, it’s because the War Museum has screwed up, not me.

Here is the truth – so please Ottawa, use it and stop making our veterans look stupid. They were far too busy during WWII to recall the correct aircraft they flew and then come home and display it correctly in our national museum. That is what the taxpayers of Canada pay you to do.

In 1990, I interviewed Thomas Dunn, who was the nose artist that painted the No. 432 squadron “Willie the Wolf” displayed in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. Thomas was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on 23 December 1912, and during his High School days completed a correspondence course on hand lettering. On 31 October 1941, he put away his paints and joined the RCAF. After training he was posted to No. 6 [RCAF] Group in late 1943, and joined No. 432 [Leaside] squadron at East Moor, in Yorkshire. His artistic talents were soon discovered and he became the squadron nose artist, painting his first nose art in the spring of 1944. Tom charged 5 Quid which was around $25 Canadian [a lot of money] in 1944. He first marked the aircraft skin with chalk squares and then did his outline in chalk, followed by an outline with white oil based paint.

On 6 July 1944, a new Halifax bomber Mk. VII arrived at East Moor, serial NP707 and it carried out five operations until 26 July 44, when it was involved in an accident. The repairs would not be completed until 27 August, and during this month delay Sgt. Thomas Dunn painted the nose art of “Willie the Wolf” on Halifax NP707. This was completed for the crew of P/O A. Potter J877003, who flew Willie on 23 operations until the end of their tour 1 March 1945. The Halifax was then flown by ten different crews until 25 April 1945. On 25 March 1945, it was flown by a friend of mine in Calgary, Alberta, P/O H.E. Kearl J91181 who took her to Munster, Germany.

[Harold Kearl crew photo]

[Harold Kearl photo 12 April 1945]

P/O Harold Kearl flew Willie on the aircraft’s 60 operation, a very special event as the Halifax had completed two full tours, and now Thomas Dunn would paint a second set of wings with an “O” in the centre. On 12 April, Harold Kearl had his picture taken in Willie, which now had received her second set of operational wings.

Willie was a special bomber in 432 squadron and considered very lucky to fly, she would bring you home again, which she did 67 times. This Halifax completed her 67 operations over a nine month period from 11 July 1944 to 25 April 1945, during some of the heaviest air war combat over Germany. During this time period 23 different crews flew Willie and they all survived. In the same nine month period 112 other Canadian bombers were shot down and 784 aircrews were killed or became POWs.

In January 1942, S/Sgt. Leonard Sansone drew a cartoon of a soldier with a wolf’s head, for the camp magazine “Duckboard” at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, USA. This wolf soldier had a one-track mind on sex, and a play [double-standard] on words, which became an immediate hit, and by 1943 had expanded to 1,600 camp newspapers including England and Canada. In England, so many foreign servicemen were seeking a romantic encounter with the British ladies, it was like they were being stalked by a pack of wolves. The wolf took the name “Willie” and this had a major effect on WWII nose art in America, Canada and England. Today the War Museum collection has three nose art panels related to this Willie Wolf, and No. 432 had one.

On 26 July 1944, No. 415 [Swordfish] squadron was redesigned from Coastal to Bomber Command squadron and arrived at No. 62 Base East Moor, to share the base with No. 432 squadron. They received a new Halifax Mk. VII, serial MZ632, code letters 6U-W.

This is where the problem began and continues today in the Canadian War Museum.

The crew from No. 415 squadron walked across the same field at East Moor and ask Thomas Dunn if he would paint the same nose art on their Halifax serial MZ632. Tom was paid his 5 Quid and the work begin, which looked the very same as his original “Willie the Wolf” including the same name. However, it is very easy to spot when you compare the style of the bombs painted for operations, and the Nazi fighter shot down by 415 aircrews.

[Author collection]

This is the Halifax VII, serial MZ632 that flew with No. 415 [Swordfish] Squadron as 6U-W, and became the 2nd painted by Thomas Dunn. It flew 47 operations and was scrapped England in January 1947. The nose art was ‘not’ saved.

This is the 1st nose art painted by Thomas Dunn and today is in the War Museum – Ottawa, Halifax VII, serial NP707, QO-W.

During my interview with nose artist Thomas Dunn in July 1990, he had no idea his original art work survived, he in fact believed it was scrapped. I informed him that F/L Lindsay had toured the grave yard at Croft, and picked his panel for shipment to Canada. It arrived in May 1946, and went into storage at Hull, Quebec, until 10 June 1976. This was the largest original nose art in the world, 11′ 3″” wide by 5′ 1″ high, and the RCAF Officer’s Club Mess on Glouster St., Ottawa, wanted it. They were loaned this huge nose art panel, where it remained, [seen only by Air Force Officer’s] until 8 May 2005.

On 7 August 1991, original artist Thomas Dunn and his nose art meet for the first time in 46 years. This is the photo he sent to me, very proud RCAF veteran, but still forgotten today. On 25 May 1945, P/O Harold Kearl was assigned to ferry Halifax “Willie the Wolf” to the graveyard at Rawcliffe, in his log book he wrote -“W” Willie the Wolf graced the sky for the last time. She was no longer needed as the war was over. I flew her to the Handley-Page, Clinton Dome, near Yorkshire, her birthplace and to her end. Hundreds of aircraft were assembled there to be scrapped. Such a fatal ending for a Halifax bomber that gave so much to so many Canadians in Yorkshire, and all over the wartime skies of Germany and Europe.

Harold Kearl had no idea another RCAF [Harold] officer would come along and save this nose art. A few weeks later F/L Lindsay took his three photos and marked the nose art for shipment to Canada. It was cut from the Halifax nose by Goodwin, crated and placed on a ship for Canada. It arrived on 7 May 1964, and today graces the wall in the War Museum. Harold Kearl has never made it to Ottawa to see his old bomber art. He was the very last RCAF pilot to fly her in WWII, and today in lives in Calgary, Alberta.

I am very proud to have met the artist and be a close friend of pilot Harold Kearl.

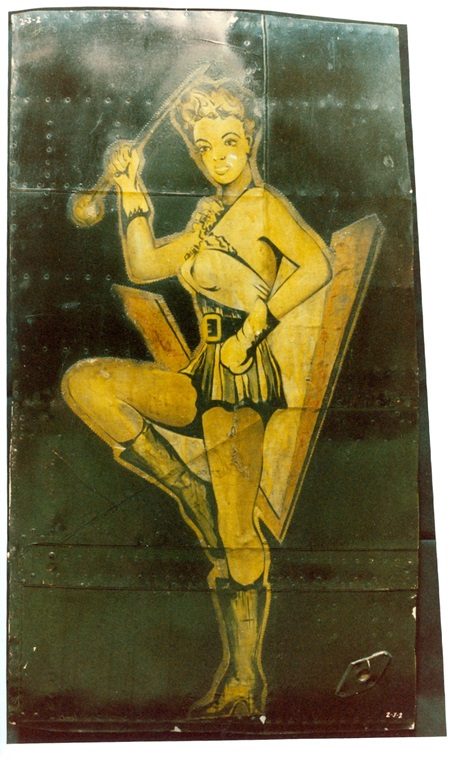

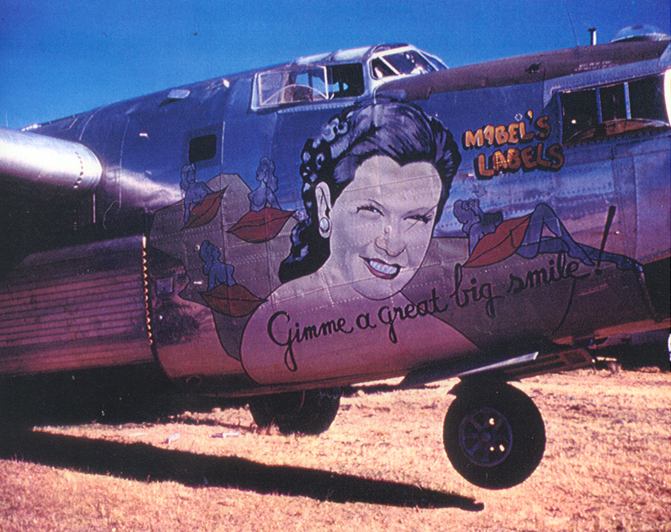

This is the first image taken by Lindsay roll #5, print #1, [Negative RE77-83] which is a new roll of film and besides the nose art, he captures the bomber line parked wing-tip to wing-tip on the perimeter track that runs around Clifton, possibly early June 1945. These bombers on the perimeter are still intact, while the bombers on the main runways have lost their wings, engines, and tail, only the fuselage remains. The New Halifax was delivered to No. 426 [Thunderbird] Squadron on 14 July 1944, but flew no operations. It was transferred to No. 408 [Goose] Squadron on 3 August 1944, and flew her first operation to Saint-Leu-d’Esserent two days later. The nose art was not painted directly onto the skin, but in fact was painted on fabric, possibly original Wellington bomber skin. The nose art is then glued to the nose of the new Halifax Mk. VII, serial NP714. On the aircraft’s third operation, 8 August 44, she is piloted by the crew of F/O R. E. Johnson, and from this date on it becomes their aircraft. The names are painted for each crew member – “MAC” F/O Paddy Wilson, Bomb aimer, “THE HEAD” F/O Gene Messmer, navigator, “THE VOICE” F/Sgt. Scott, wireless, “ROMEO” pilot – F/O Robert Johnson, “SMITH” Sgt. Bruce Devlin [RAF], “Doc” F/Sgt. Gordon McKnight, rear gunner, and “JERKS” F/Sgt. Kierstead [Dutch] Mid-upper gun.

Rear L to R – Sgt. Bruce Devlin, [British Flight Eng.- plus supplied photo image of crew], F/Sgt. Gordon McKnight, [R-Gun] F/Sgt. Scott [Wireless], F/Sgt. Kierstead, [Dutch Mid Upper gun]

Front row L to R – F/O Paddy Wilson, [Bomb Aim] , F/O Robert Johnson [pilot], and F/O Gene Messmer [Navigator].

Lindsay takes a second image of the complete Halifax, roll #5, print #2 [negative RE77-82]. He then marks the nose art for salvage and today it is in the War Museum collection.

Without research and recorded history, the above photo gives very little information in regards to location, who took the photo, and why it was parked on the air strip. That has been supplied at the beginning of my story but now let’s just look at the aircraft and markings without any history.

The Halifax has a serial number NP714, code letters EQ-A, a number of bombs and a nose art lady over a large letter “V”. You can guess the large “V” is for victory and that is about all I had for many years. On 22 October 2005, I made email contact with the British Flight/Engineer, Bruce Devlin at Heron Hill, Kendal, Cumbria, UK and that changed everything. To my complete surprise Bruce had no idea “his” WWII Halifax nose art still existed in Canada. I explained to him he was not alone, as thousands of RCAF veterans had no idea ‘their’ original panels existed, as they had been in storage for the past sixty years, and only went on public display 8 May 2005. These panels had flown over 700 operations during WWII, by 300 different air crews, made up of 2,100 Dutch, French, American, British, French-Canadians and Canadians in the RCAF. Bruce was suddenly coming to Canada to see his original art, but he never made it. Weeks later [3 Dec.] his son Stewart Devlin sent an email to advise me his father was serious ill and on doctor’s orders he could not travel. Bruce joined thousands of others who missed the chance to see their Halifax aircraft nose art, due to the fact it is not seen as an important historical paintings. How sad.

Bruce however left his mark in regards to missing history, and proved the value to interviewing and learning the truth from WWII veterans. Bruce had no idea where the nose art came from, it was all done by the ground crew. I believe the ground crew cut the original nose art from a Wellington bomber and when you study the original in Ottawa, you clearly see the zigzag scissor cut marks. The original code letters for Halifax NP714 were EQ-V and that is why the Drum Major girl is over a large “V”, and why the ground crew picked her. The Johnson crew gave her a name, which was never painted on the aircraft, but to them she was “Veni” [I Came], “Vedi” [I Saw], “Vici” [I Conquered]. All the bomb operations featured a “V” with a bomb painted over it, and they completed 25 operations in their Halifax, the last on 6 December 1944. Bruce advised me the aircraft was damaged two days later and when I checked the Lindsay files it confirmed that date, plus the damage was repaired on Christmas eve, 24 December 44 and she returned to 408 squadron with code letters EQ-A. All these facts are confirmed in the Lindsay photos.

On 6 December 1940, the Canadian Government passed the War Exchange Act, which banned all non-essential goods from being imported to Canada. This included all American comic books and resulted in the birth of Canadian comics started by Cyril and Gene Bell in Toronto. The “Bell” Bros. published the first, most, and best of the Canadian “Whites” and by May 1945 had printed over 20 million. The Drum Major nose art girl originated from one of the Bell comic characters who appeared with a fictitious Canadian big band leader “Drummy Young”. Young was fighting the evils of Hitler and featured many scantily dressed girls and drum major female marching band leaders. In 1946, the War Exchange Act was abolished and slowly the American comic publishers lured the Canadian artists to work south of the border. By 1947, the Canadian Comic book industry was destroyed, but one memory from the past still remains in the War Museum at Ottawa.

What’s that old saying – “A pictures worth a thousand words” in this case it’s the reverse, but will anyone in Ottawa listen?

Original image from Simonsen collection taken at No. 408 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Edmonton, Alberta, 1986.

Today she is in the War Museum and you can see she was painted on what appears to be original fabric doped aircraft skin.

This RCAF Halifax nose art shows a very good perspective in the effect a good painting had on a number of different squadrons in WWII.

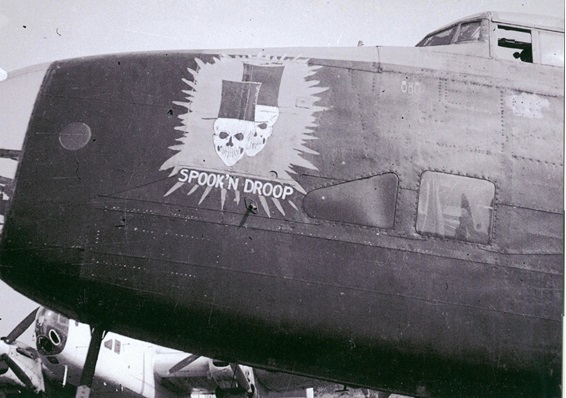

When F/L Lindsay snapped this image he also captured a white Coastal Command Halifax in the background. The image appeared on roll #5, print #3, and became negative RE77-84.

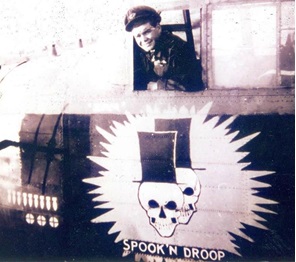

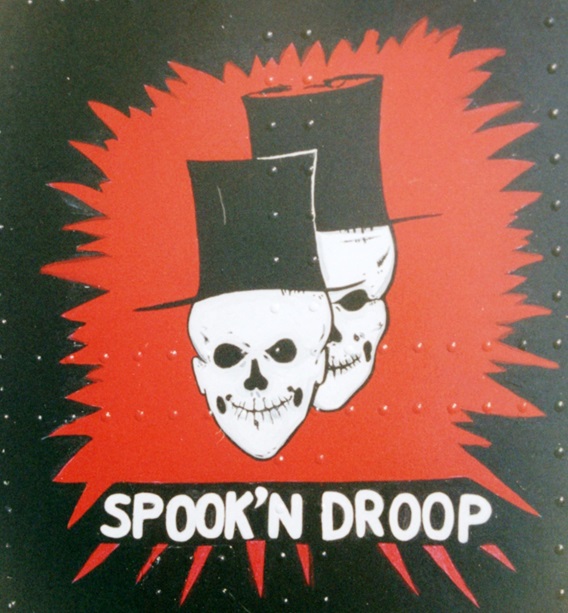

This Halifax Mk. III, serial LV860 was built between 10 January 1944 and 25 February 44, first delivered to No. 35 Squadron RAF and then went to No. 10 Squadron RAF. On 31 July 1944, it was transferred to the Canadians in No. 6 [RCAF] Group and began her new career assigned to No. 415 Squadron, and then on that same date it was sent to 427 [Lion] squadron, and received the code letters KW-U. The impressive ‘death heads in top hats’ was painted on LV860 by a nose artist in No. 427 squadron. No. 427 squadron began converting to the British built Lancaster B. Mk. III’s in March 1944, and the original crew of Halifax LV860, “Spook’ N Droop” received a new Lancaster in July 1944, serial ME501, code KW-T. On their new Lancaster, the aircrew ask the same nose artist to repaint his original art of Spook’ N Droop, which he did.

On 2 August 1944, the Halifax LV860 was transferred to No. 429 [Bison] squadron and the original nose art remained. She flew operations until 5 December 44, and then was damaged in a Cat. “C” accident. Repaired on 14 January 45 she returned to 429 squadron and again was transferred to No. 420 [Snowy Owl] squadron on 16 March 1945. The following day she was transferred to No. 425 Squadron and flew until 21 April 1945, when she was involved in a second Cat. “A” accident. The Halifax still carried her original nose art when she was sent for disposal on 31 May 1945. The aircraft arrived at No. 43 Group Rawcliffe on 8 June 1945 for scrapping.

The records by F/L Lindsay are very important as it shows he arrived at No. 43 Group some date after 8 June 1945. The Halifax was scrapped on 16 June 45, now I know Lindsay took his photo in one of the eight days between those dates. This nose art was not saved by Lindsay, as far as I know.

Simonsen replica donated to Western Canada Aviation Museum, Winnipeg, in 2009

To this point I have attempted to show the world [Internet] just a small selection of what F/L Lindsay saved for Canada, in May and June of 1945. He was not paid or ask to save this nose art collection, it was done for his love of Canada, including his Government, and he alone realized how extremely important it was to preserve this art for historical merit. Lindsay recorded a total of 63 black and white nose art images, and 54 were flown by the RCAF in WWII. Many of the crews who flew in these Halifax bombers would later be killed in other aircraft. I have turned 70 years of age and since 1977, I have attempted to save this huge Canadian Nose Art History, and have it properly displayed, with a complete history including a wall to honor the artists who painted the aircraft. No luck. The Americans have one complete Museum which holds the World’s Largest Nose Art collection of 33 panels, and it honors everyone from pilot, ground crew and most of all the artists who painted aircraft in WWII.

collection Clarence Simonsen

In Ottawa this has proved to be a -“LOST CAUSE” as Canadians just don’t care.

I now wish to show another forgotten part of what Lindsay did and saved on film. Nine of the Halifax bombers he recorded on film were not RCAF but French, Australian and British. I had to pay for all these nose art images, so feel free to use.

The most famous Halifax nose art from Australia, from which I received wonderful letters and info.

Please look in the background and notice the other Halifax aircraft parked awaiting the chop.

Yes, I know and have recorded the history of each Halifax, and now I would just like to see the reaction to these last three photos.

The famous RAF Halifax LV917, “Clueless” flew 100 operations and was soon scrapped. Her sister aircraft “Friday the 13th” was rebuilt as a complex composite, and can be seen in Yorkshire Air Museum today, a tribute to the British who built and flew this famous bomber during WWII. The original nose art panel [plus others] are displayed in the world class Imperial War Museum, London, England. The same RAF nose artist painted both “Friday the 13th” and “Clueless”.

Clueless

During my 37 years of original RCAF nose art panel research, I learned the main collection of ten original nose art images saved by F/L Lindsay remained in storage somewhere in Hull, Quebec. I could never get permission to see or photograph. In 1977, it was my first visit to the old War Museum where I met the curator Mr. Hugh Halliday, and to this man I owe many thanks. He was the person who spared my research and informed me I could see one original panel from the RCAF collection, in fact the largest, and it was located at the RCAF Officer’s Mess on Glouster St., Ottawa. This panel had just gone on display 10 June 1976, so thanks to Mr. Halliday, I became very lucky.

Due to the fact I was a Toronto Police Officer, they allowed me into the building, and just seeing this huge WWII nose art image made me realize what Lindsay had done for Canada. In the mid-1980s I also located the three missing panels which had been loaned to No. 408 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Edmonton, Alberta. These images were taken in 1986, and appear in this article. There is one other man who is very, very important to this collection being gathered and put on display in the new War Museum. The only person in Ottawa who would listen to my story was Mr. Daniel Glenney, Director of Collections Management and Planning of the War Museum. He listened and arranged to have the four missing panels returned to Ottawa. I met with Mr. Glenney in November 2004, and he gave me a tour of the new War Museum and showed me the original nose art panels hanging on the wall, but no history. He informed me he was retiring in 2005, and honestly felt the nose art would never be given its rightful place in Canadian RCAF WWII history. He told me the hard facts, the War Museum contains hundreds of “Official” wartime paintings, by official war artists who were hired and paid by the Canadian Government to record war scenes. The bureaucrats in charge of the War Museum have no interest in WWII RCAF nose art, period. I found this is also reflected by many of the post-war feelings held by many RCAF senior Officers, who have powerful control over our Canadian museum’s displays.

This nose art is displayed in Ottawa today, mostly forgotten, along with the complete Lindsay history. We have the postwar RCAF Officers, the politicians, and most of all the glory seeking bureaucrats, who run today’s Aviation Museums and treat them as if they were their own collection. It’s all about their title, “Curator”, “COE”, “President”, plus the six figure salary, and less and less about the RCAF veteran in WWII.

Ottawa, we have a problem.

Remarkable! Going to have to read this over a few times to digest the wealth of information 🙂

It took me a long long time to format Clarence’s article.

So much information but it was worthwhile because I wanted to make it available for someone who is researching this subject.

As a footnote…

One of the planes on this article… I have written about it in 2012.

http://425alouette.wordpress.com/2012/11/11/jour-du-souvenir-2012/

Reblogged this on RCAF 425 Les Alouettes and commented:

Un article de Clarence Simonsen, fruit de ses recherches depuis 37 ans!

On y parle de l’escadrille 425 et du Halifax d’Antoine Brassard.

Such imagination and creativity went into these brave heroes of past. A rather long post for you, but worthwhile with the history content wrapped up in here!!

I know it’s rather long… 43 pages were sent by Clarence…

I just had to lend a helping hand.

I learned a lot in return.

What a fabulous presentation. I can only imagine the importance of nose art in a world of regimentation and control.

Impressive isn’t?

A real wealth of information here, shame Only a few people had the good foresight to save what they could before the axe man came.

Quite a story. More stories from Clarence later.

What an awesome job of collecting and interpreting the huge amount of information on Nose Art from “Mr. Nose Art” Clarence Simonsen. I can’t express enough how much the two of you have continually contributed to keep this history available to Canadians and I just wish more current RCAF members, politicians and citizens would get together and push our Government to do something to acknowledge these artists and men like F/L Lindsay. And thereby give the deserved credit to the men and women who served in the RCAF during WWII and those that lost their lives so we can live the way we do. Thank you so much for all you do and please do not stop, there has to be someone out there with influence who can initiate some action.

I will relay this comment to Clarence Simonsen. I know he will appreciate.